BLEEDING PROBLEMS IN BITCHES DURING HEAT PERIOD AND HOW TO CONTROL IT

Most dogs have their first heat when then are about 6 months old, but this varies a lot and can be as late as 2.5 years old. From then on, most dogs have a heat every 6-7 months (approximately twice a year). Most dogs have bigger gaps between their seasons as they get older, but unlike humans (who at some point go through the menopause), dogs continue to come into heat throughout their whole lives unless they are speyed. Once a dog has been speyed, her seasons stop and she can no longer become pregnant. Being on heat isn’t painful, but can make a dog feel uncomfortable, unsettled and ‘under the weather’. Although some people think that a dog’s bleeding during their season is a dog’s period, it’s actually a sign that they are at their most fertile.Most breeds have their first heat at about 6 months old but it may be earlier or later.

A heat can usually be identified when there is some bleeding from the vagina, a swollen vulva or increased urination. Female dogs do not produce very much blood however, and in a small dog you may not even notice the bleeding.

Estrous Cycles in Dogs

When does a female dog have her first estrous (heat) cycle?

Female dogs will have their first estrous (reproductive or heat) cycle when they reach puberty. Each cycle consists of several stages; the stage called estrus refers to when the female can become pregnant. Often, a dog that is in the estrus stage is said to be in heat or season.

On average, puberty (or sexual maturity) is reached at about six months of age, but this can vary by breed. Smaller breeds tend to have their first estrous cycle at an earlier age, while large and giant breeds may not come into heat for the first time until they reach eighteen months to two years of age.

What Is the Dog Heat Cycle?

The dog heat cycle, also known as the estrus cycle, is a biological event where a female dog is most receptive to mating. It usually lasts anywhere between two and four weeks, and a female dog will experience this about every six months. A dog in heat may exhibit strange personality and physiological changes throughout the cycle.

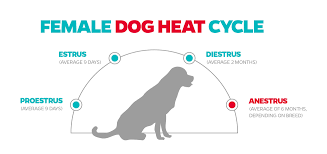

There are four stages:

- The proestrus stage:This is the first stage of a dog’s heat cycle and usually begins with the swelling of the vulva. It can last anywhere from three to 17 days. A female dog in this stage of the heat cycle is resistant to male company and may exhibit changes in personality, appetite, and more frequent tail tucking.

- The estrus stage:A female dog will begin to naturally follow her breeding instinct in the estrus stage of her heat cycle. She is the most fertile here as her ovaries release eggs for fertilization and she is most willing to accept male company in this stage. She’ll raise her rear toward male dogs and may remain in this stage for between three and 17 days.

- The diestrus stage:In this stage, the dog’s heat cycle begins to come to an end. If a female dog entering this stage has been impregnated, this stage will last from the end of the estrus stage up until her puppies are born (about 60 days). A female dog will not flirt as much and her swelling will decrease gradually.

- The anestrus stage:This is the stage of the dog’s heat cycle that lasts the longest, anywhere between 100 and 150 days. The anestrus stage is also known as the resting stage. The dog’s heat cycle starts again after this stage.

How often does a female dog come into heat?

Most dogs come into heat twice per year, although the interval can vary between breeds and from dog to dog. Small breed dogs may cycle three times per year, while giant breed dogs may only cycle once per year. When young dogs first begin to cycle, it is normal for their cycles to be somewhat irregular. It can take up to two years for a female dog to develop regular cycles. No time of year corresponds to a breeding season for domesticated dogs except for Basenjis and the sled dog breeds, which typically tend to cycle in the spring.

What are the signs of estrus?

The earliest sign of estrus is swelling or engorgement of the vulva, but this swelling is not always obvious. Bloody vaginal discharge is often the first sign that an owner notices when their dog comes into heat. In some cases, the discharge will not be apparent until several days after estrus has begun. The amount of discharge varies from dog to dog.

The vaginal discharge will change in color and appearance as the cycle progresses. At first, the discharge is very bloody, but it thins to become watery and pinker in color as the days pass. A female dog in heat will often urinate more frequently than normal or may develop marking behavior in which she urinates small amounts on various objects either in the home or when out on a walk. During this phase of her cycle, the urine contains pheromones and hormones, both of which signal her reproductive state to other dogs. This is how dogs in heat attract other dogs, particularly males.

Male dogs can detect a female in heat from a great distance and may begin marking your property with their urine, attempting to claim their territory.

How long does estrus last?

Although it can vary by individual, the average length of the estrus stage is 10-14 days.

At what stage of the estrus cycle can the dog get pregnant?

The female dog usually ovulates at about the time that the vaginal discharge becomes watery; this marks her most fertile stage and is the time when she will be most receptive to breeding. However, sperm can survive for a week in the reproductive tract and still be capable of fertilizing the eggs, so she can get pregnant at any point while she is in estrus. Contrary to popular belief, it is not necessary for the female to tie with the male dog to get pregnant (for further information see the handout “Estrus and Mating in Dogs”).

How long does pregnancy last in a dog and when can pregnancy be detected?

Pregnancy in dogs lasts approximately nine weeks (63 days).

How can I prevent my dog from becoming pregnant?

The best way to prevent your dog from becoming pregnant is to have her surgically sterilized (spayed) by ovariohysterectomy or ovariectomy before she has her first estrous cycle. Since it can be difficult to predict when this first cycle will occur, most veterinarians recommend performing the procedure before the dog is six or seven months of age.

What can I do if my dog has been mismated or accidentally mates with another dog?

Contact your veterinarian as soon as possible. There are mismating injections that can be used within the first two days after mating, but there are risks associated with their use. Your veterinarian will discuss your options and any risks associated with them.

Should I let my dog have an estrus cycle or a litter of puppies before spaying her?

There are no valid reasons for letting a dog have a litter of puppies before she is spayed. Newer research has shown that some larger breeds (e.g., Labrador Retrievers, Golden Retrievers, and German Shepherds) may benefit medically from delaying their spay surgery until after their first heat cycle; however, the consensus at this time is that spaying will increase the lifespan of a dog. Dogs can become pregnant on their very first estrous cycle, increasing the risk of accidental breeding. Dogs are indiscriminate, so a brother may breed with his sister, a father may breed with his daughter, and a son may breed with his mother.

A common belief is that female dogs will become more friendly and sociable if they have a litter of puppies. This is not true and only serves to contribute further to the serious problem of dog overpopulation.

How to Tell If a Dog Is in Heat

As a pet parent, it’s a good idea to verse yourself well on the signs of a dog entering their heat cycle. Common signs of a dog entering heat include:

- Frequent urination:This is one of the most common signs that a dog is entering heat, especially if they’re uncharacteristically urinating in the house.

- Vaginal bleeding and/or discharges: A female dog entering heat may lightly discharge and/or bleed from her vagina while entering the proestrus stage. The bleeding will grow heavier and lighten in color as she enters the estrus stage.

- More attention paid to male dogs:If a female dog in heat sees a male dog, she’ll “flirt” with him by exposing and raising her rear in his direction while moving her tail out of the way.

- Excessive genital licking: A female dog in heat will excessively lick (or “clean”) her genital area.

- Nervously aggressive behavior: Since a female dog in heat is secreting mating hormones, she may exhibit unusually aggressive behavior.

Other signs of a dog in heat include tail tucking and the swelling of the vulva.

What to Do When Your Dog Is in Heat

You should never panic if you notice your dog entering her heat cycle; it’s a very natural occurrence! There are simple steps you can take to make sure your dog gets the special care she’ll need.

- Do not leave your dog outside and unsupervised:A female dog in heat who’s also outside and alone is the perfect company for a passerby (or stray) male dog looking to mate.

- Walk your dog with a leash:To safely walk your dog while she’s in heat, you should always keep her on a leash despite her obedience skills. A female dog in heat will be heavily influenced by her hormones.

- Increase indoor supervision:You should stay mindful of your dog’s whereabouts and keep her off furniture, as she may naturally leave some blood spotting behind and potentially stain surfaces. Pads can also be used to allow her to enjoy her preferred resting spot without the risk of leaving stains behind on furniture or carpet, and providing for easier cleanup at regular intervals.

- Use diapers and washable diaper liners to prevent messes: Some bleeding or bloody discharge is normal during her time in heat, and she will likely have the need to urinate more frequently than you are used to. Use diapersto contain and prevent messes, and help both of you navigate this period without unwanted stains or accidents. There are multiple types of diapers for dogs in heat to choose from, including disposable and reusable garments. Wee-Wee Disposable diapers work much like a diaper for a human infant, plus include a special opening to accommodate your pet’s tail. They’re available in multiple sizes so you can find the one that’s right for your dog, ranging from X-Small to X-Large. Proper sizing is important to prevent leakage.

Deploying these four care tactics when your dog is in heat will ensure she has a safe, clean, and manageable experience.

Why Bleeding From the Vagina Occurs in Dogs

There are a few reasons why your dog may be bleeding from her vagina (vulva). Blood in the urine may indicate a urinary tract infection but differs from blood that passes from the vulva and is usually present within a voided urine sample.

Estrus Cycles

Unspayed females will go through two to three estrus cycles annually, also known as ‘going into heat’. A heat cycle lasts two to three weeks and begins as spot bleeding from the vulva. Your dog’s vulva will also become swollen, and she may urinate more often than normal. Her excessive urination is meant to attract male dogs. Estrus cycles are not a medical condition but a natural reproductive cycle in dogs.

Pyometra

Pyometra is a medical condition that may arise during or, more typically, after, an estrus cycle and is an infection in the uterus. Pyometra is a serious, life-threatening condition that requires immediate medical treatment. As your dog’s hormones change during her heat cycles white blood cells, which prevent infection, are not permitted into the uterus. The uterine lining will grow in anticipation of pregnancy. However, if pregnancy does not occur within several consecutive heat cycles, cysts can start to grow within the thickened tissue and create an ideal environment for bacterial growth. Without the white blood cells present to combat the bacterial growth, your dog can develop a uterine infection.

Miscarriage

Your dog may become pregnant during her estrus cycle, and after a few weeks, her body may abort the pregnancy due to a number of reasons. Miscarriages will often result in excessive bleeding from the vagina where your dog may pass the placenta and other tissues.

Vaginal Inflammation

If your spayed female is experiencing vaginal discharge that contains blood, she may be suffering from vaginal inflammation or vaginitis. Additional symptoms of vaginitis include frequent urination or difficulty urinating. Your dog may also lick her vulvar area more frequently and scoot her bottom across the floor. Vaginitis is usually caused by an infection or foreign body and can affect any female at any age although prepubescent and older dogs appear more predisposed.

Vaginal Tumors

Unspayed females are more likely to develop vaginal tumors as they age. Most vaginal tumors are benign, or non-cancerous and can cause vulvar bleeding as well as blood in the urine, vaginal odor, and difficulty giving birth.

HORMONAL CONTROL OF ESTROUS IN BITCHES

PROGESTOGENS

Synthetic analogues of progesterone, also termed progestins or progestogens (PG), are pharmaceutical compounds commonly used to control the reproductive cycle of domestic animals The following PGs are commonly used in dogs and cats for temporary (starting the treatment shortly before proestrus onset) or prolonged (starting in anestrus) postponement of estrus, or for suppression of estrus (starting the treatment after proestrus onset) : medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), megestrol acetate (MA), proligestone (PR), chlormadinone acetate (CMA), delmadinone acetate (DMA), norethisterone acetate (NTA) and melengestrol acetate (MGA). From the clinical point of view all these product act in the same way through a block of the production and/or release of GnRH from the hypothalamus. These compounds show a variety of action on the reproductive and endocrine system (such as hyperplasia of the endometrium, hyperplasia of the mammary parechima, decreased production of adrenocorticosteroids, increased secretion of prolactin and growth hormone, insuline resistance) as well as some local skin reactions at the injection site and behavioral modification (increased appetite and weight, polydipsia, slight depression, decreased libido in males). In pregnant bitches and queens use of PGs may cause masculinization of female fetuses if administered early in pregnancy (during organogenesis) or delayed parturition if administered in the last decade of pregnancy.

Clinical considerations for a safe use of progestogens

All the above cited effects are reversible and do not generally cause problems in healthy young to adult animals treated for not too long and using the recommended dosage. In general, a treatment period of 6 months is considered adequate in most individuals, although longer treatments can also be safe provided that the female is given a rest of 1-2 months every 4-6 months. While most bitches and queens may tolerate well treatment periods of more than 6 months, animals with a preexisting disease such as subclinical diabetes, microscopic mammary lesion/tumor or cystic endometrial hyperplasia may see their condition worsen rapidly as a result of the PG treatment. The following is a series of considerations on patient selection and type of presenting complaint for which a PG treatment should or should not be used.

Do not use long acting compounds (such as MPA or PR or any other compound marketed for long term use) prior to puberty in felines, as this may cause the queen to develop a long-lasting mammary hypertrophy which could become a life-threatening situation. In prepuberal animals it is best to use initially a short acting compound (such as MA) per os for 12 weeks and then change to a long acting PG once potential side effects have been ruled out.

Do not treat pregnant females, as this may cause fetal developmental defects as well as delayed parturition, thereby causing fetal death in utero due to placental ageing and detachment.

Do not treat pseudopregnant bitches. During a PG treatment clinical signs of pseudopregnancy will disappear but will recur once treatment is discontinued, and the problem may worsen.

Do not treat a female during diestrus. The stage of the reproductive cycle should always be identified using vaginal cytology and/or serum progesterone assay, and the bitch or queen should best be treated during anestrus. Diestrus should be ruled out in felines too, as approximately 30% of queens ovulate spontaneously, maintaining thereafter a 30-45 day-long diestrus.

Do not treat females with uterine haemorrhage. Prolonged sanguineous vulvar discharge following parturition in the bitch can be a critical problem which should either be treated with a uterine contractive drug (i.e., as ergonovine) or sent to surgery. Milder bloody vulvar discharge can be caused by uterine neoplasia, cystic endometrial hyperplasia with superimposed endometrial inflammation, pyometra, metritis. None of these conditions will benefit from administration of a progestogen.

Do not treat diabetic patients. Although not always necessary, it would be wise to measure blood glucose before and/or after a prolonged treatment to confirm health status with regard to glucose metabolism.

Do not use PGs in females with prolonged heat. A prolonged heat may be due to ovarian cyst(s), a granulosa cell tumor, or may be due to a split heat (in the bitch) or to a misinterpretation of normal estrous signs by the owner. For none of these categories is a progestogen treatment indicated (although in some cases an ovarian cyst may benefit from administration of a progestogen). Therefore, bitches or queens with a prolonged heat should not be treated with a progestogen, unless a diagnosis of cystic ovarian disease has been carefully confirmed and surgery or administration of GnRH or hCG are not a valid therapeutic option.

Choosing the right candidate

The ideal candidate is an adult postpuberal female in anestrus. Prepuberal females should not be treated long acting compounds because of the risk of precipitating a subclinical uterine, endocrine or mammary condition (such as diabetes, cystic endometrial hyperplasia-pyometra in the bitch or mammary hyperplasia in the queen) which are rare but have been reported in young animals. If one of the above conditions is present the administration of a long acting progestogen prior to diagnosis may pose a serious health threat on the female. A minimum database of clinical information to be gathered prior to administering a long-acting compound should include:

collecting a thorough reproductive history to rule out occurrence of estrus within the last 1-2 months (which would mean that the female is in diestrus);

a complete clinical exam;

palpation of the mammary gland to rule out presence of mammary nodules;

a vaginal smear to rule out presence of oestrus.

Table. 1 shows the suggested dosages of the most commonly used progestogen-based compounds in the bitch and queen.

Table 1. Suggested dosages of the 3 most commonly used progestogen compounds in bitches and queen for the control of estrous.

| Suggested Dosage | Dog | Cat |

| Medroxyprogesterone Acetate |

2.5-3.0 mg/kg IM every 5 months | 2.0 mg/kg IM every 5 months for the feline |

| Megestrol Acetate | <2.0 mg/kg administered for <2 weeks in proestrus, or <2.0 mg/kg administered for a longer duration of time in anestrus. A typical dosage for estrus suppression is 2.0 mg/kg/day for 8 consecutive days, while a typical dosage for temporary postponement is 0.5 mg/kg/day in late anestrus. | <5.0 mg/cat administered every other day for < 3 weeks or with a slower rate of administration. |

| Proligestone | 10-33 mg/kg SC every 3, 4, 5, 5 months | 10 mg/kg SC every 3, 4, 5, 5, months |

ANDROGENS

Androgens are also widely used for the control of estrous cycle in dogs and cats, although less information is available on most of the active principle commercially available for veterinary use. In the male, androgens cause a block of spermatogenesis (due to degeneration of seminiferous tubular epithelium), an increase in libido, a higher incidence of priapism, and growth of prostatic tumors. In the female, the main reproductive effect of androgens is to cause suppression of ovarian activity thank to a negative feedback on the pituitary which decreases gonadotropin secretion; the ovaries of dogs treated with an androgen such as mibolerone will contain primary and secondary follicles but few that mature to ovulatory size. Androgens will also cause atrophy of mammary gland/endometrium and lactation arrest.

Mibolerone (originally marketed by Upjohn as Cheque drops®) was until recently the only androgen approved for estrus suppression in bitches in the United States. Mibolerone is not recommended for use in breeding animals by the manufacturer. The suggested dose of mibolerone is based on weight and breed of the dog with German Shepherds receiving the highest dose, 180 µg once daily per os, regardless of body weight. Mibolerone should not be administered to Bedlington Terriers. Estrus suppression can be achieved starting the treatment at least 30 days before onset of the next proestrus and for as long as estrus suppression is desired. Prolonged postponement can be achieved for up to 2 years, but the drug has been demonstrated to be safe and effective even if used for up to 5 years. Return to estrus averages about 70 days, with a range of 7 to 200 days.

There are no published reports describing fertility after treatment with mibolerone, although most bitches seem to exhibit apparently normal fertility after its use. The most commonly reported side-effect of androgens in female dogs is clitoral hypertrophy, which occurs to some degree in 15 to 20% of dogs treated with mibolerone. Other reported side-effects of androgens include creamy vaginal discharge, vaginitis, increased mounting and aggressive behaviour, anal gland inspissations, musky body odor, obesity, and epiphora. Androgens are contraindicated in potentially pregnant bitches, as they may cause masculinization of female fetuses; in prepuberal bitches, in which they may precipitate premature physeal closure, and in dogs with renal or hepatic diseases (Olson et al., 1986a). Presence of intranuclear hyaline bodies in hepatic cells and, rarely, changes in liver function tests have been described in dogs after treatment with mibolerone; clinical significance of hepatocellular changes is unknown.

Testosterone also has been described for estrus suppression in bitches. Successful regimens reported include injection of 100 mg testosterone propionate once weekly, oral treatment with 25 to 50 mg methyl-testosterone twice weekly, and subcutaneous implantation of at least 759 µg/kg. Testosterone, methyltestosterone and nandrolone are currently used with indications such as oestrus suppression, false pregnancy, lack of libido as well as with other non-reproductive indications (renal insufficiency, anemia, post-surgery etc.). Testosterone propionate (100 mg once weekly) and methyltestosterone (25-50 mg twice weekly per os) are currently marketed in some European countries for oestrus suppression. Canine false pregnancy can safely be treated with androgens as it does not recur following cessation of treatment unlike what happens with progestins.

GnRH AGONISTS

More recently subcutaneous implants of GnRH analogues have been positively tested in domestic and wild carnivores and felids. Leuprolide acetate (75 µg/kg IM every 28 days for 10 months), goserelin acetate (60 µg/kg IM every 21 days for 12 months) and more recently deslorelin acetate (one single implant of 6 mg causes lack of return to oestrus for 5-18 months) have shown promising results, especially considering that fertility is re-gained a few months following cessation of treatment. These products are not commercially available yet for veterinary use. Leuprolide is marketed in Europe as a human drug under commercial names such as Enantone®, Lucrin®, Carcinil®, Ginecrin®, Procren®, Procrin®, Prostap®. Goserelin is commercialised as Zoladex®. Deslorelin is awaiting approval from governmental authorities in Australia for veterinary use in dogsa dn cats.

Compiled & Shared by- Team, LITD (Livestock Institute of Training & Development)

Image-Courtesy-Google

Reference-On Request.