Care & Management of Heat Stroke in Dogs

Starting mid-April, the mercury level has started rising across India. The scorching heat, dryness or humidity (depending on where you live) will have a big impact on our pets. Let’s look at how heat affects our pets, and what we can do to minimise seasonal distress.Unlike humans, pets cannot sweat through their body surface; they depend completely on panting to cool themselves. Though some amount of sweating takes place through the paws and nose, it’s minimal. Due to these differences pets are more prone to heatstroke.It is not just people who get affected by the soaring summer heat. Pets and strays suffer too. From dehydration to fungal infection, they have many woes coming their way.

Pets, strays and even birds need a lot of care to avoid heat strokes and stay healthy during summer. Heatstroke/hyperthermia is a life-threatening syndrome seen in human beings, dogs and other species. It occurs particularly under humid and hot condition (Coris et al., 2004 and Bruchim et al., 2006). Hyperthermia is the elevation of body temperature due to excessive heat production or absorption, or to deficient heat loss, when the causes of these abnormalities are purely physical. The upper border of the thermo neutral zone – the upper critical temperature – is the effective ambient temperature above which an animal must increase heat loss to maintain thermal balance. The body temperature reaches above 105–106˚ F. During hyperthermia, endotoxemia and activation of the coagulation cascade reaction leads to disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and multiorgan dysfunction (MOD) the organs most commonly affected are the brain, kidney, liver, heart and skeletal muscle (Bruchim et al., 2006). Heat stroke is often complicated by acid-base imbalance, cerebral edema and blood clotting mechanism. Heat stroke requires early detection, aggressive therapeutic intervention and continuous critical care monitoring to avoid any secondary complications and death. Heatstroke is characterized by two components, namely (1) elevated core body temperature and (2) CNS abnormalities and dysfunction.

Dogs don’t sweat like us humans, instead they release heat by panting and also by sweating through their paw pads and nose. If they are unable cool themselves enough their internal body temperature begins to rise. Hyperthermia is the term used to describe this elevation in body temperature.

There are three different types of hyperthermia – heat stress, heat exhaustion and heat stroke. While it common for people to use these terms interchangeably, the conditions are different, varying in severity.Heat stress is the less severe heat related illness. At this stage, dogs will show an increase in thirst and panting. As the condition worsens, it will progress to heat exhaustion then, finally, to heat stroke.

All heat related illness require immediate attention. Heat stroke, the most severe of heat related illnesses, is a very serious condition that can lead to death even with intensive care.

Officially summer has started , you can already see your pets panting, sitting under the fan. One general rule you need to keep in mind is that if it is hot for you, it is hot for them as well. From heat strokes to tick infestations to skin irritation, your pet is susceptible to many ailments during these few months, most of which can be avoided with minimal efforts.

Our pets are covered with hair and their body temperatures are much higher than that of humans. Moreover, they do not sweat to cool off, they pant and look for cool surfaces to cool down. There’s quite a few guidelines you can follow to maintain the well-being of your four-legged kids during these oncoming months.

First their walk times. Try to do their walks early morning and only towards late evening when the sun is going down. Avoid the scorching heat during late morning hours and early evenings. The asphalted roads and the melting heat is as uncomfortable to them as they are for you. Try to walk them on soft grounds or grass instead of the roads. Take extra care of their paws. Keep them clean and also apply paw cream at home during night time.

Secondly, when it comes to food and water intake keep a sharp eye on your little one. The natural inclination for them is to eat less so kindly do not get alarmed if you see your pet eating much lesser than his usual habit if he is otherwise fit and active and healthy. Do not force feed. Dogs tend to eat less in summer but they end up spending more energy in an effort to lower their body temperatures.

A lot of pet owners tend to feed curd and buttermilk to their pet during summer, but it is very important to note that this food contains more water (70-80%) and does not have adequate levels of energy, vitamins, minerals, etc. Make sure they’re fed a well-balanced nutritionally complete and energy dense diet. One also needs to provide them with plenty of fresh water in summer and increase the frequency of feeding to ensure that your pet is fed the total recommended quantity of pet food. Dehydration can have disastrous effect on your pooch. Give him fruits like watermelon (de-seeded, of course), cucumber and others.

During summer there are a number of seasonal dangers you and your dogs should look out for. The first are parasites, which can be found at their highest numbers in summer. Ticks, fleas, mosquitos and more are all rife through the warmer months and are something that can cause real problems for your pet. Make sure your dog is protected from these parasites through the use of different flea treatments, shampoos and sprays. Diligently brush them every day. Grooming is essential too, especially for long- coated dogs. Though trimming by a professional might be fine, do not shave your pet’s coat.

Heat stroke is a possibility. As a rule, puppies and elderly dogs in summer tend to be more susceptible, as are dogs with thick, heavy coats or dogs with an existing cardiovascular or respiratory condition. Certain breeds with narrow airways, such as bulldogs, pugs are particularly prone to heat stress. If you’re worried about any form of heat stress, the best course of action is always to seek prompt veterinary attention, helping you to avoid potential complications.

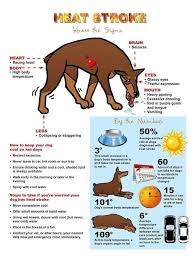

If you notice any of these signs/symptoms in your pet during summer, these may be the first signs of a heat-related problem:n Excessive panting or gasping for breath seeking shade n Reduced food intake, reduced activity n Muscle spasms/muscle tremors n Fatigue, weakness, vomiting n Diarrhea and depressionThe hallmark of heat-stroke is severe central nervous system disturbance. Get your dog to a cool location, provide small drinks of cold water, and, if he doesn’t improve within a few minutes, contact your veterinarian.

Causes

Excessive environmental heat and humidity. A rise in body temperature happens when the ambient temperature increases above 86˚F. Break down of the animal‟s thermal equilibrium occurs when the body temperature reaches 104˚F. At 106°F the brain becomes involved and permanent damage may develop. Dogs that are chained outdoors are commonly affected due to non availability of drinking water and shade. Due to this the animal becomes excited, which further induce the heat stroke. Heat stroke is rare in dogs which are left free regardless of exercise and environmental temperature. Poor ventilation of dog house and pets left in locked cars are the most critical factor for development of heat stroke (Larson and Carithers, 1983). Neurogenic hyperthermia due to damage in hypothalamus. Upper airway disease, paralysis of larynx, heart and/or blood vessel disease, nervous system and/or muscular disease and previous history of heat-related disease Poisoning; some poisonous compounds, such as strychnine and slug and snail bait, can lead to seizures, which can cause an abnormal increase in body temperature Anesthesia complications Excessive exercise.

Pathogenesis

Heatstroke may increase the metabolic rate which depletes liver glycogen stores rapidly and further increase in endogenous metabolism of protein. Anorexia is due to respiratory embarrassment and dryness of mouth. Increased heart rate is due to increase in blood temperature, decreased blood pressure and peripheral vasodilation. Increase respiratory rate and depth is due to direct effect on high temperature on respiratory centre, which indirectly cools by increase the salivary secretion, rate of airflow across the respiratory epithelial surface. Oliguria results from decreased renal blood flow and peripheral vasodilation. When the critical temperature is exceeding there is circulatory failure due to myocardial weakness, depression of nervous system activity and respiratory centre. Respiratory failure leads to death. The imbalance between heat generation and dissipation is impacted by thermoregulation, acclimatization, acutephase response (APR), production of heat shock proteins (HSPs), and a patient‟s predisposing factors (Bouchama and Knochel, 2002).

Predisposing factors

More common in brachycephalic breeds (short nosed and flat face), long thick hairy breeds, young ones, aged animals, previously affected animals. Other risk factors are obesity, poor heart / lung conditioning, hyperthyroidisim, insufficient water intake, restricted water diet and dehydration. Forced exercise during times of high environmental temperature.

Clinical signs

Clinical signs vary based on the duration and degree of exposure to elevated environmental temperature. The clinical signs are panting, increased body temperature (105-1070 F), drooling of saliva, haematemesis, black or tarry colour stools, seizures, muscle tremors, wobbling, incoordination, involuntary paddling, oliguria, turbid and scanty brownish urine (Ettinger and Feldman, 2001). Dark Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci (2019) 8(5): 365-371 367 urine described as “machine-oil” or “cokecolored” may be present, indicating myoglobinuria (Flournoy et al., 2003). Dehydration, tacchycardia with thready pulse is usually present due to extreme hypovolemia. Pulse deficits may be noted if there is an arrhythmia (Johnson, 1982). Breathing distress, reddened gums, small pinpoint areas of bleeding indicates disseminated intravsacular coagulopathy. Shock, change in mental status and unconsiousness are also noticed. However, it should be pointed out that some animals may have a normal or even subnormal temperature at the time of examination. This occurs especially if the owners have initiated treatment to cool down the animal before presentation or if the patient is in an advanced stage of shock (Drobatz and Macintire, 1976). Clinical presentation can sometimes give clues as to whether the animal‟s elevated temperature is pyrogenic or nonpyrogenic. Pyrogenic hyperthermia includes infectious and noninfectious systemic inflammatory diseases. Systemic inflammatory diseases characterized by elevated temperature without panting and hypersalivation in dogs. Pyrogenic animals will usually be ambulatory, whereas many heatstroke animals are unwilling or unable to rise (Miller, 2000).

Signs and symptoms of heat stress in dogs

There are two commonly associated signs and symptoms of heat stress in dogs. These include:

- Increased thirst

- Increased panting

If your dog is unable to regulate their body temperature, their heat stress may progress to heat exhaustion. Signs of heat exhaustion include:

- Heavy panting

- Weakness and episodes of collapsing

If treatment isn’t given during heat exhaustion, it is extremely likely it will progress to heat stroke, the most severe case of heat illnesses. Signs and symptoms of heat stroke include:

- Change in gum colour (bright red or pale)

- Drooling

- Dizziness or disorientation

- Dullness and collapse

- Increased heart rate and respiratory rate

- Vomiting and/or diarrhoea

- Muscle tremors

- Seizures

Clinicopathological findings

Haematological changes

Hemoconcentration (elevated hematocrit and total solids) associated with dehydration is commonly seen. Low total solids and anemia may be found in some dogs as a result of direct hyperthermic damage, gastrointestinal losses, vasculitis, or renal losses. Thrombocytopenia, prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time, prothrombin time, increased fibrin degradation products, decreased fibrinogen levels, and prolonged activated clotting time can be seen individually or in combination during DIC. Schistocytes may be present on a blood smear, lending support to a presumptive diagnosis of DIC. There may be increased leukocyte numbers; however, severely affected dogs may exhibit marked leukopenia. In addition, blood smears may reveal nucleated red blood cells however, this finding is transient.

Biochemical changes

Hypoproteinemia; decreased blood glucose concentration is noticed because of increased metabolic demands, hepatic dysfunction or even sepsis. Elevated BUN and creatinine, especially during an acute renal failure crisis. In addition, prerenal factors may contribute to azotemia through dehydration, poor perfusion and hemoconcentration. Hepatocellular damage usually results in elevated liver enzyme concentrations, particularly aspartate transaminase, alanine transaminase and alkaline phosphatase. Mild hyperbilirubinemia may also occur. High levels of creatinine phosphokinase indicate rhabdomyolysis and may reach peak at 24 to 48 hours before declining.

Urine analysis

In urinalysis increased urine specific gravity, proteinuria, hematuria were observed. Urine sediment should be examined for casts (cellular casts, epithelial cells) indicating renal tubular damage. Myoglobinuria is occasionally noted on urinalysis and indicates rhabdomyolysis.

Electrolyte abnormalities

Hypernatremia is frequently present due to pure water loss. A mild hyperkalemia may also be present. Hypophosphatemia and hypocalcemia may occur as well, although the mechanism of these changes is unknown. Blood gas analysis may reveal respiratory alkalosis reflecting hypocarbia secondary to metabolic acidosis reflecting lactic acid production associated with poor tissue perfusion or excessive muscle activity. Metabolic acidosis in dogs with heatstroke may also be caused by diarrhea or acute renal failure. In addition, mixed acid–base disorders (e.g., respiratory alkalosis, metabolic acidosis) commonly occur. Frequent monitoring of blood gases or total carbon dioxide is recommended during the initial resuscitation of heatstroke patients.

Differential diagnosis

Heat stroke must be differentiated from eclampsia, hypoglycemia, encephalitis, convulsions, and similar conditions. The sudden onset of signs with high rectal temperatures (excess of 105°F) is usually sufficient for diagnosis (Diehl et al., 2000). Ingestion of tremorgenic toxins such as hexachlorophene, mycotoxins on walnuts or moldy cheese, organophosphates, or metaldehyd has been reported to cause hyperthermia.

TREATMENT

The immediate step is to reduce the body temperature. Spraying the dog with cool water or immersing the dog in cool – not cold – water can be carried out, as this may cause constriction of blood vessels near the surface of the body and may decrease heat dissipation. Total submersion in cold or ice water can cause shock, so one should douse legs, belly, nose, and neck with cool water. The dog’s extremities should be rubbed during cooling to promote peripheral circulation. Gradual cooling is always best (Lewis, 1970). Cool the dog with evaporative cooling (such as isopropyl alcohol on, groin, under the forelegs and foot pads) or fan. Allow the dog to drink cool water freely. If possible, the dog should be sprayed down by the owner before being transported to the veterinary hospital. Evaporation can be enhanced by driving with the windows open or placing the dog by the air conditioning vent as this will help with convective heat dissipation. The rectal temperature should be monitored every ten minutes. When the temperature reaches 103˚F stop cooling with water and wrap the animal with wet towel. Oxygen supplementation via mask, cage or nasal catheter may be used for severe dyspoenic patients, or a surgical opening into the windpipe or trachea may be required if upper airway obstruction is an underlying cause or a contributing factor. After recovery affected animals should always be maintained in a cool (70°F) oxygen chamber for 24 hours. A systemic, broadspectrum, bacteriocidal antibiotic is often administered on the assumption that patients are predisposed to infection. Crystalloid fluids (e.g., balanced electrolyte solutions) are usually the initial fluids of choice because of the need to rehydrate the interstitium. Colloids (e.g., hetastarch, dextran, plasma) may be used during the initial resuscitation period followed by crystalloid therapy shortly thereafter. When both types of fluids are used together, the dose of crystalloids should be reduced 40% to 60% (Kirby and Rudloff, 1997). If peripheral circulatory failure, hemoconcentration, shock or DIC are noticed lactated Ringer’s solution are the fluid of choice administered at a rate of 90 mL/kg BW/hr which corrects dehydration and associated hypovolemia (Tilley and Smith, 2000). Calcium gluconate for possible hypocalcemia resulting from hyperventilation and alkalosis can be administered. Dexamethasone @ 1.0-2.0 mg/kg body weight can be administered to treat shock and potential cerebral edema. However, treatment with corticosteroids is controversial, as they may induce gastrointestinal ulceration, immune suppression and exacerbation of heatstress induced renal damage. However, corticosteroids (prednisolone sodium succinate, dexamethasone sodium phosphate) may prevent cerebral edema and stabilize

membranes in some patients experiencing shock. Studies demonstrated that glucocorticoid administration reduced interleukin-1 concentrations and resulted in neuroprotective effects in rats with heatstroke (Liu et al, 2000). NSAIDs, such as dipyrone and flunixin meglumine are contraindicated for heatstroke because they can cause severe hypothermia, gastrointestinal ulceration, prolonged bleeding time, and bone marrow suppression (Mathews, 2000). Mannitol 2.0 g/kg body weight as a 20 % solution over a 10 minute period may be used if the patient is stuporous or comatose but should be administered cautiously if DIC is suspected. Gastric and peritoneal lavage with a cold solution. If mean blood pressure falls below 60 mm Hg after fluid resuscitation, dopamine or dobutamine hydrochloride should be considered. Doses should be adjusted according to blood pressure monitoring and clinical response. Septic shock should be considered if the animal remains hypotensive after fluid resuscitation. To protect the GI tract H2 blocker, such as cimetidine or ranitidine, may be given one hour after administration of sucralfate. Administration of oral medications in debilitated patients with potentially compromised swallowing reflexes may cause aspiration and therefore, should be used with caution .

What to do if your dog has heat stress

If you believe your dog may be experiencing heat stress follow these steps:

- Move your dog to a shaded spot, or even to an air conditioned room

- Offer fresh, cool water

- Stop all physical activities until their symptoms have resolved

Should your dog’s symptoms worsen, or you think your dog is suffering from heat stroke, you must take immediate action. Steps to take include:

- Begin cooling your dog by wetting down their body with a hose or bucket, but avoid the face

- A fan blowing over their damp skin will assist in cooling them down

- See a vet immediately

- It is not advised to place wet towels over the body as it will trap the heat that is trying to escape

Tip: recruit others to help you – ask someone to call the vet while others help you cool your dog.

How to prevent heat stress in dogs

Prevention Avoid taking your dog out during the peak temperatures of the day, or leaving the dog in places that can become too hot for your dog like a garage, sunny room, sunny yard or car. Never leave your dog in a parked car, even for only a few minutes, as a closed car becomes dangerously hot very rapidly. Always have water accessible to your dog. On hot days provide ice blocks for your dog to lick. If your dog is old or is a brachycephalic breed it needs special attention. Educating the public and clients about the dangers of exercising and confining pets in environments is conducive to heatstroke. Preconditioning pets is necessary. (i.e., exercising regularly and starting out slowly in warm and humid weather until acclimatization occurs).

There are ways you can prevent heat stress from happening, such as:

- Don’t leave your dog alone in the car on a warm day, even if the windows are open. The inside of cars act like an oven – temperatures can rise to dangerously high levels in a matter of minutes.

- Avoid exercise on warm and humid days

- When outside, opt for shady areas

- Keep fresh cool water available at all times

- Certain types of dogs are more sensitive to heat – especially obese dogs and brachycephalic (short-nosed) breeds, like pugs and bulldogs. Use extreme caution when these dogs are exposed to heat even with a short walk to the shops or sitting at a cafe

Precautions to take

1. Avoid exposure to the hot sun by keeping pets indoors or under shade, especially, during peak temperatures (noon to 4 pm).

2. Ensure that your pet drinks plenty of water throughout the day.

3. All outdoor activities, like exercising or walking should be restricted to either early morning or late evening.

4. Don’t let your pet climb hot surfaces during walks as it will heat up their body quickly and burn their sensitive paw pads.

5. Never leave your pet in the car in this weather, as he will be prone to heat stress.

6. It is better to trim long haired breeds, but never shave them completely as the coat also provides protection against sun and heat.

7. Flat-/short-faced breeds like Pug, Shi-Tzu, Bulldog and Boxers are prone to heat stress as they cannot pant effectively like long-faced breeds. Pups, seniors, obese dogs and pets suffering with heart or respiratory tract issues should be kept in cool temperatures as much as possible.

8. Ensure supervision if you are leaving your pet in a swimming pool to beat the heat.

9. Keep a check on your pet’s vitals, and as soon as you notice any change in him or observe any signs of heat stress, consult your veterinarian rightaway.

Feeding routine

-Did you know that the energy requirement in pets increases with increase in ambient temperature? As dogs use panting to lower their body temperature, they need additional energy in summer.

– Since pets spend a lot of energy during summer one should ensure that their feeding levels are not reduced and they consume an energy-dense balanced diet.

– Feeding only curd rice (which is high on moisture with 70-80% water) during summer will not meet their daily energy, mineral and vitamin requirements. You may often see your pet tired and lacking energy.

-If your pet is on dry food, try mixing it with gravy/wet food; it adds moisture and is easy to eat. Keep the food quantity in check while adding gravy.

-Feed them during the cooler parts of day, early morning (before 8 am) and late evening (after 7 pm). You may also consider giving them smaller meals by increasing the number of meals to accommodate the daily requirements.

—DR. SHANKER SINGH,TVO,GALUDIH

https://www.pashudhanpraharee.com/care-management-of-heat-stroke-in-dogs/heat-stroke-in-dog/

https://www.pashudhanpraharee.com/management-of-heatstroke-in-dogs-3/

https://vcahospitals.com/know-your-pet/heat-stroke-in-dogs

REFERENCE-ON REQUEST.

https://www.rspca.org.uk/adviceandwelfare/pets/dogs/health/heatstroke