ROLE OF SUSHRUTA, SHALIHOTRA , NAKUL & SAHDEVA IN ANCIENT INDIAN PASHU AYURVEDA

A tradition of veterinary therapy developed very early in India. Based on Ayurveda, Indian veterinary medicine is known for its specialised literature, which provides information on methods of preventing and treating animal diseases. Some of these treatments are still practiced today. The World’s First Animal Hospital was established in India(Emperor Asoka’s Period).The Practice of Animal Healing, existed in India even centuries prior to the Emperor Asoka’s regime, as evident from the life of the ancient saints of the Tamil Kingdoms & Dravidian Civilizations and from the Rishi’s & Sadhu’s of Aryan Civilizations in Northern India. Keeping these rich traditions alive for several centuries and even today, the Indian Subcontinent boasts one of the richest biodiversity of animal and plant life in India.

Ancient Indian literature in the form of the Vedas, Puranas, Brahmanas, epics etc. is flooded with information on animal care, health management and disease cure. Atharva veda is a repository of traditional medicine including prescriptions for treatment of animal diseases. Scriptures such as Skanda Purana, Devi Purana, Matsya Purana, Agni Purana, Garuda Purana, Linga Purana, and books written by Charaka, Susruta, Palakapya (1000 BC), and Shalihotra (2350 BC) documented treatment of animal diseases using medicinal plants. Yajur veda cites importance of growth and development of medicinal plants and Atharva veda details the value of medicines in curing the diseases and provides interesting information about ailment of animals, herbal medicines and cure of diseases.

During Mahabharata period (1000 BC), Nakula and Sahadeva, the two Pandava brothers were experts of horse and cattle husbandry, respectively. Lord Krishna was an expert caretaker and conservator of cow husbandry. The ancient Indians were so apt with the knowledge of herbals, even Alexander acquired some of the skills used by Indians, particularly for treatment of snakebite. Graeco-Romans imported livestock from India after invasion by Alexander. These descriptions are available in Indika, a book authored by Megasthenes, the ambassador of Seleucus Nikator, king of Mecedonia, in the court of Chandragupta Maurya. King Ashoka (300 BC) erected the first known veterinary hospital of the world. He arranged cultivation of herbal medicines for men and animals in his empire and adjoining kingdoms. In the Arthashastra, composed by Kautilya, the guide and political advisor of Emperor Chandragupta Maurya, a lot of information is available about different animal departments – grazing lands, livestock products like skin and fur, and veterinary jurisprudence.

The history of veterinary medicine in India is closely related to the development of human medicine. Ancient Indian literature is flooded with information on animal care. The treatment of animal diseases using Ayurvedic medicine has been mentioned in many ancient Indian texts. There had been evidence on the existence of literature on veterinary science in Rigveda. The nucleus of veterinary science (PashuAyurveda) existed in Atharvaveda. Before the advent of modern Veterinary science, the ethno-veterinary practices were popular in India since time immemorial. The same physicians attended both man and animals in ancient India. Physicians treating human beings were also trained in the care of animals. During the early Vedic period Asvini Kumars, the well-known physicians of deities were also expert in Pashu-Chikitsa. Indian medical treatises like Charaka Samhita, Susruta Samhita, and HaritaSamhita contain chapters or references about care of diseased as well as healthy animals. There were, however, physicians who specialized only in the care of animals or in one class of animals only; the greatest of them was Shalihotra, first known veterinarian of the world and the father of Indian veterinary sciences. Salihotra composed three texts in Sanskrit. Perhaps the practice of animal and human treatment acquired status of separate profession during later Vedic and epic period with the emergence of prominent veterinary experts including Salihotra, Palkapya, Rajpaputra and Nakula. The treatment of animal diseases using Ayurvedic medicine has been mentioned in Agni Purana, Atri-Samhita, Matsya Purana, Skanda Purana, Devi Purana, Garuda Purana, Linga Purana and many other texts. The veterinary treatment of infection of skins, horns, ears, tooth, throat, heart and navel, hemorrhagic problems, dysentery, digestive ailments, cold, parasitic diseases, stomach worms, rabies, anemia, wounds and medicines to increase milk production has been given in detail. The treatment of animal diseases in ancient India was well-developed and carried out with great care and accuracy by well-trained personnel. According to the Susruta Samhita skillful surgeons treated animals with great perfection. Various techniques of surgical operations along with instruments have been dealt in detail in Shalihotra’s and Palakapya’s works. Medicinal herbs like arjuna (Terminalia arjuna), kutaja (Holarrhena antidysenterica), kadamba (Anthocephalus cadamba), sarja (Vateria indica), neem (Azadirachta indica), ashoka (Saraca asoca), asana (Pterocarpus marsupium) etc. were used widely to cure ailments of men and animals. The earliest available works on elephantology were Hasti-Ayurveda and the Gajasastra. Both were attributed to sage Palkapya. Palkapya was the ultimate authority on elephants in India. He dealt with the anatomy, physiology, disease and management of elephants in detail. His Hasti-Ayurveda has 20,000 slokas, dealing with elephant medicine and surgery. In the postVedic literature came up Asva-Ayurveda – about horses,Gau- Ayurveda- about cows and Ayurveda about hawks. The veterinary science has been mentioned in the Charakasamhita also. It has further been elaborated in Haritasamhita. GarudPurana mentions a number of Ayurvedic medicines used against ailments of animals. The AgniPurana regarded the sage Palkapya as the expositor of the elephant science. Sage Gautama composed the GautamSamhita which dealt with the treatment and management of cow. In the Arthashastra composed by Kautilya, the guide and political advisor of Emperor Chandragupta Maurya, a lot of information is available about different animal departments, grazing lands, rules of meat science, livestock products and veterinary jurisprudence. Buddhism respects equality between human beings and animals and tries to solve everyday life difficulties. Biographies of the period of Buddha likeBuddhaCharita authored by Asvaghosa reveal the fact that Lord Buddha was a great animal lover and conserver. Inscriptions, as those of Ashoka, provide information on the veterinary and animal husbandry practices in those times. During the regime of King Ashoka, many well equipped veterinary hospitals were built, probably the first ever in the world in 238 BC. During his reign, Veterinary hospitals were state institutions and medicinal herbs were made available for treatment. He arranged cultivation of herbal medicines for men and animals in his empire kingdom and adjoining kingdoms.The present-day Veterinary Council of India adopted its insignia, the sculpture of a bull and a part of the text of the stone edict from the period of Emperor Ashoka (around 300 BC). Ashoka gave veterinary science a new turn in India.

Why the Indian Veterinary History is important…

- According to Somvanshi’s Documentation(2006)on Indian History of Veterinary Medicine, Cattle husbandry was well developed during the Rigvedic period (1500–1000 BC)

- Atharvaveda provided an interesting information about ailments of animals, herbal medicines, and cure of diseases.

- Shalihotra, the first known veterinarian of the world, was an expert in horse husbandry and medicine and composed a text Haya Ayurveda.

- Sage Palakapya was an expert dealing with elephants and composed a text Gaja Ayurveda.

- In Mahabharata period (1000 BC), Nakula and Sahadeva, the two Pandava brothers were experts of horse and cattle husbandry, respectively.

- Lord Krishna was an expert caretaker and conservator of cow husbandry. Gokul and Mathura were famous for excellent breeds of cows, high milk production, quality curd, butter, and other products.

- Buddha was a great protector of all kinds of animals and birds (including game) in ancient India as he preached lessons of non-violence to masses.

- Graeco-Romans imported livestock from India after invasion by Alexander. These descriptions are available in Indika, a book authored by Megasthenes, the ambassador of Seleucus Nikator, king of Mecedonia in the court of Chandragupta Maurya.

- The great king Ashoka (300 BC) erected the first known veterinary hospitals of the world. He arranged cultivation of herbal medicines for men and animals in his empire and adjoining kingdoms.

- In a famous text, the Arthashastra (science of economics) composed by Kautilya, the guide and political advisor of emperor Chandragupta Maurya, a lot of information is available about different animal (elephant, horse, and cow) departments, grazing lands, rules of meat science, livestock products like skin and fur, and veterinary jurisprudence. This knowledge flourished during the great Hindu kings of the Gupta period up to 800 AD before Islamic followers invaded India.

- Many books were written on veterinary science during an ancient time in India which are as follows:

| Name of the Book | Name of the Author |

| Ashwa Shastra | Prince Nakula |

| Ashwayurveda | Acharya Shalihotra |

| Gaja lakshana | Brihapati |

| Gajayurveda | Acharya Palakapya |

| Gaja Darpan | Hemadri |

| Gavyayurveda | Prince Sahadev |

| Hastayurveda | Acharya Palakapya |

| Manasollas | Someshwar |

| Matanga lila | Nilkantha |

| Mrugpada Shastra | Hamsadev |

| Nakula Samhita | Prince Nakula |

| Shalihotra | Bhoja |

| Siddhopdesh sangrah | Gana |

- Most books are not available today and some are still in their original manuscript.

Elephant Medicine or Gaja Ayurveda

The Gautam Samhita, the Ashva Ayurveda and Hastya Ayurveda are the only treatises on animal science till now. Palakapya, an authority on elephant medicine belonged to the Rig vedic period and wrote Hastya Ayurveda or Gaja Ayurveda dealing with elephant medicine and dedicated to Lord Ganesha. Elephant medicine and surgery were divided into four parts, viz., Maha Rogsthan or major diseases, Ksudra Rogasthan or minor diseases, Salyasthan or surgery, and materia medica-diet and hygiene. Hastya Ayurveda also mentions about anatomy of elephant, treatment of different kinds of diseases, training of elephant, and also classification of elephants on the basis of a number of characteristics.

Equine Medicine or Haya Ayurveda

Salihotra is known to have been a specialist in the treatment of horses. He composed a treatise called Haya Ayurveda or Turan-gama-sastra or Salihotra Samhita, a work on the care and treatment of the horses. Haya Ayurveda is said to have been revealed to Salihotra by Brahma himself, the fountainhead of all knowledge. Two other works, namely Asvaprasnsa and Asvalaksana Sastram, are also attributed to Salihotra.

Veterinary medicine is theoretically divisible into eight branches, corresponding to the eight divisions set out in the Âyurveda – general surgery, general therapeutics, ophthalmology and otorhinolaryngology, care of foals (corresponding to Âyurvedic pediatrics), toxicology, fortifying treatments, demonology, and the use of aphrodisiacs.

Apart from surgical interventions, therapeutics usually consisted of the administration of medicinal preparations by different routes and in various forms: mixtures of powders, decoctions, electuaries, ointments and snuff. The principle remedies cited by the texts were based on plants, but some substances of animal or mineral origin were also used. All these natural ingredients served to prepare thousands of remedies, often of very complex formulation. The complexity of preparations is explained by the care taken to combine ingredients in order to counterbalance, enhance or prolong the effects of some ingredients through the effects of others. There are basic preparations to which various other ingredients are added to adapt the treatment to a given species. For example, the passage in the Carakasamhitâ (Siddhisthâna, XI, 20-26) concerning enemas for elephants, camels, cattle, horses and sheep provides a basic formula composed of the following plants: Acorus calamus L., Glycyrrhiza glabra L., Piper longum L., Randa spinosa Poir., Saussurea lappa C.B. Clarke. A dozen other plants may be added to these basic ingredients for elephant enemas. For cattle preparations, addition of decoctions of Butea monosperma (Lam.) Kuntze, Cedrus deodara (Roxb.) Loud. and Terminalia chebula Retz. was recommended. Other plants were indicated for horse enemas, such as Baliospermum montanum Muell.-Arg. or Croton tiglium L.

Cattle Management

Cattle husbandry was well developed during the Rig vedic period and the cow (Kamdhenu) was adored and considered the ‘best wealth’ of mankind. Vedic seers laid great emphasis on protection of cows.

Rig veda is replete with references to cattle and their management (Nene and Sadhale, 1997). References can be found on grazing of livestock, provision of succulent green fodder and water to drink from clean ponds, and livestock barns. Dogs were used to manage herds of cows and in recovering stolen cows.

In Krishi-Parashara (c. 400 BC), a description of a cattle shed is found. Cleanliness of the shed was emphasized. To protect animals from diseases, cattle sheds were regularly fumigated with dried plant products that contained volatile compounds (Bedekar, 1993).

Arthashastra mentions a government officer called the superintendent of cattle whose exclusive duty was to supervise livestock in the country, keep a census of livestock, and see that they were properly reared. The text directed that all cattle be supplied with abundant fodder and water and gives an elaborate description of ration that a bull, cow or buffalo should be supplied with. Maintenance of pastures around villages was encouraged. Manu presented that, “on all sides of a village, a space of 100 dhanus or three samya throws (in breadth) shall be reserved for pasture.” Fodder crops were cultivated and processed into silage – an old process in the Indian subcontinent as the word suyavasa in the Rig veda indicates. Cultivators also provided hay for their stock. In Agnipurana, kings were encouraged to preserve the breed of the cattle in the country.

Cow Medicine or Gau Ayurveda

Voluminous treatises are also available on cows, e.g., ‘Gau Ayurveda’. Mantras in Vedas (Shala Nirman and Goshth Suktas of Atharva veda) describe that the animal houses (Goshth) and their management were of good quality. Pashu Samvardhan Sukta of Atharva veda indicates that Vrihaspati Deva knew the animal behaviour and management well. Treatment of weak, infertile and unproductive cows for making them productive was well described.

Remedies still in use

Several Indian laboratories now make preparations from ancestral recipes for the treatment of domestic animals. Many of these medicaments are polyvalent, due to the multiplicity of ingredients used in their preparation. For example, a stomachic and tonic containing 59 ingredients from Ayurvedic texts is produced by a company in Bangalore. This preparation is recommended for treating digestive disorders (anorexia, dyspepsia, constipation, etc.) in cattle, sheep, goats, horses and dogs, in doses proportional to the size of these animals.

Another example is provided by an ointment against sprains and sores, prepared from the following plants: Abrus precatoriusL., Acorus calamus L., Celastrus paniculatus Willd., Hyoscyamus niger L., Moringa oleifera Lam., Nardostachys jatamansi D.C., Ocimum sanctum L., Saussurea lappa C.B. Clarke and Vitex negundo L. To these oils are added extracts of seven other plants: Anacyclus pyrethrum D.C., Colchicum luteum Baker, Curcuma amada Roxb., Gloriosa superba L., Litsea sebifera Pers., Myrica nagi Thunb. and Nerium odorum Sol. All these plants have been investigated and their active principles are known (1,6). Nardostachys jatamansi is often combined with oil of henbane (Hyoscyamus niger) as an antineuritic. Ocimum sanctum and Vitex negundo are used as wound dressing. In traditional medicine, the root of Curcuma amada is applied to contusions and sprains. Extract of Colchicum luteum is applied externally as an analgesic.Many plants of the Ayurvedic pharmacopoeia have since been shown to be effective.

Shalihotra

Shalihotra was considered to be the founder of veterinarian science in Indian tradition.In an age when horses were crucial for wars, transport and to display courtly wealth, it was Shalihotra who created what appears to be the very first horse care manual. Equestrian veterinary medicine attained a glorified status in ancient India. Equine veterinarians of the day began to be known as ‘Shalihotriya’, so widespread was his influence and teachings.

Veterinary Science dates back to ancient India, 3rd Century. A big name in Indian Veterinary Science is of Shalihotra, founder of Indian Veterinary Science.

Shalihotra, was born in the area of Sravasati, in Uttar Pradesh. He was born to Hayagosha. He compiled scriptures about care and management of Horses in his book named ‘Shalihotra Samhita – Encyclopedia of Sahalishotra’.

Samhita consists of anatomy, physiology, surgery, diseases and cures composed in different 12,000 shlokas (verses) in Sanskrit, which was later translated in Persian, Arabic, Tibetan and English languages. His work elaborated different body structures of horse species and identified the structural difference of teeth which can help in determining the age of the Horse. He also wrote Asva-prashnsa and Asva-lakshana, respectively.

The practice of maintaining livestock and domestic animals has been a centuries old tradition in India. Cattle was useful for sustenance and powerful beasts like horses and elephants came in handy during turf wars. It was only natural then that a body of works would be developed dealing with the care and management of these creatures. This was the rudimentary origin of veterinary science in human history. Ancient literature, including the Vedas and Puranas, reveals that animal medicine existed in India 3,000 to 4,000 years ago. Veterinary science as it was practiced then was theoretically divided into eight subjects; general surgery, general therapeutics, ophthalmology and otorhinolaryngology (the science of the ear, nose and throat), care of foals, toxicology, treatments, demonology and the use of aphrodisiacs.

The foundation of veterinary science in India can be attributed to Shalihotra, a 3rd Century BCE expert on animal rearing and healthcare. He is known for composing the Shalihotra Samhita, which was based on Ayurveda and extensively documented the treatment of diseases using medicinal plants. This knowledge was believed to have been revealed to Shalihotra by Lord Brahma himself. The principal subject matter of the Shalihotra Samhita is the care and management of horses. The treatise consists of 12,000 verses and has been translated into Persian, Arabic, Tibetan and English. It describes equine and elephant anatomy and physiology, with a laundry-list of diseases and preventive measures. It also details the body structure, elaborates on breeds and contains notes on the auspicious signs to watch for while buying a horse. Though Shalihotra has composed other treatises on the care of horses, the Samhita is the earliest known work on veterinary science in India.

Subsequent veterinary works were largely based on the Shalihotra Samhita, which future authors either revised or built upon. Soon after, veterinarians came to be known as salihotriya. The welfare of animals was considered important and it was the duty of veterinary doctors to prevent infections in animals, which might spread to human society. According to the Arthasastra by Kautilya, veterinarians were also posted on battlefields to tend to injured animals. During peace time, these doctors had to ensure that only healthy animals were sent to the markets to prevent the breakout of infections and diseases. It is believed that King Ashoka set up the first veterinary hospital in India. He set aside lands for the cultivation of herbal medicines for men and animals alike. Medicines were administered in the form of powders, decoctions and ointments. Although herbal plants were the main ingredients in medicines, animal-derived substances and minerals were also used.

Just as Shalihotra is considered the expert on horses, Muni Palkapya is considered the authority on elephants in India. He too explored the anatomy, physiology, diseases and management of elephants. His treatise came to be known as the Hastya-Ayurveda or Gaja-Ayurveda and was dedicated to Lord Ganesha. He dealt with topics such as elephant medicine and surgery, and prescribed methods for the preparation of medicines and treatment for various elephantine diseases.

Several treatments and medicines mentioned by Shalihotra are still used to date, such as for digestive disorders, sprains and sores in cattle, sheep, horses and other domesticated species. It is clear from Shalihotra Samhita that the since ancient times people of the subcontinent had extensive knowledge of veterinary care, sophisticated enough to carry out surgeries even. Modern research on how we may enrich and uplift the lives of all creatures around us owes a debt of gratitude to these early practitioners of animal science.

Significance of Nakul and Sahdev in ‘Mahabharata’

Nakula and Sahadeva are referred as Asvineya, as the two physicicans of gods. Both the brothers were incarnations of Ashwini Kumaras, and possessed special set of skills.

Nakula:

Nakul was a great exponent of horselore (ashwa -vidya), whose treatise on cattle-breeding etc termed as “Ashwa chikitsa” is also available still there. He was able to diagnose disease of horse by examining colour of urine. Twin brother of Nakul, named as Sahdev was also expert in animal husbandry. He had a skill to diagnose the disease on the basis of urine of sick bull. Both of them learnt these skills from his guru (teacher) called as Dronacharya. There are so many monographs on elephant-lore are also available. The animals like horses and elephants were the chief constituents of military of kings. Gurus (teachers) prepare their students in several sciences. If we talk about “Mahabharata” Dronacharya he made his pupils in different fields as Yudhishthir in administration, Bhim in gada,Arjuna in archery, Nakul in horse cure and Sahdev in animal husbandry. In modern time veterinary science has an important place as separate branch in medical science.

Shalihotra Samhita

He passed his knowledge of Veterinary Science to his disciple named Shusrut – First known Surgeon in the world, who devised 101 instruments and taught people the importance of Health.

Ayurveda is the science of life containing highest evolved form of life i. e human beings, who form only an insignificant number among the host of living creatures. The universal sense of Ayurveda includes the mute living creatures. It has given the veterinary science designation at par with the science that deals with ailments of man.

The birds, the animal kingdom and the vegetable kingdom, all these are the different forms of life. Ayurveda has many voluminous treatises on the vegetable kingdom, horses, elephants, bovine species, Hawks etc. as it has on the science of human life. Besides these special treatises, it is found, that general books on medicine includes some portions of veterinary science.

Father of Veterinary Science

Salihotra is described as the Father of the veterinary science. Caraka and Susruta also establishes the same kind of medical science in the veterinary branch. It’s treatise is known as Hayayurveda or Turangama-sastra or the science of horses. Thus we learn that elementary knowledge of veterinary science formed a part of general medical education. The humane spirit of Ayurveda was not enough by providing a niche for veterinary science in the vast structure of the healing lore. Veterinary science produced specialists and their treatises in its field.

Duties of a Veterinary Doctor

Veterinary physicians took every precaution against epidemics among the cattle and tried preventive as well as curative medicines. Physicians were also kept ready on the battlefield for treating the animals wounded in the war. Elephant doctors shall administer necessary medicines to elephants which while making a journey, happen to suffer from disease, overwork, rut or old age. For the welfare and health of these animals which were useful to the human being in many ways, veterinary physicians were engaged to treat the animals in their illness save the society from infection and kept the animals fit.

Supervisors of Cattle

The superintendent of cows applied remedies to calves or aged cows or cows suffering from the diseases. The superintendent of horses took care of them in the same manner. Once in six months sheep and other animals were shorn of their wool. The same rule shall apply to herds of horses, asses, camels and hogs. The injunctions were meticulous which was demonstrated in a few instances culled from our vast veterinary science and its ethics.

All the superintendents, watchmen, sweepers, cooks and others received one Prastha of cooked rice, a handful of oil and two pales of sugar and salt. The doctor would receive 10 Palas of flesh. Animals were scrupulously cared for, while on journey.

Pinjrapoles

Our modern Pinjarapoles are but the poor and dilapidated relics of these hospitals organized on humane principles. These Pinjarapoles are the reminders of the glory that was once borne by the country.

Asoka the humanitarian princes organized hospitals for animals and passed orders against cruelty to them.

Law Regulations

The physicians inspected the animals which were for sale in the market in order to prevent the spread of infection. Meat for sale in the market was also inspected and the sale of putrid or diseased flesh was strictly forbidden by means of severe punishment for such offenses. The state not only took such measures for the health of the people and the animals in this way, but it imposed fines on the physicians in charge of the animals if they committed a mistake in the treatment by carelessness or by any other reason. Ill treatment to animals or even to the vegetation was not tolerated and fines and punishment were imposed on the miscreants. Any one who sterilized animals without state permission was severely dealt with.

Visnu Samhita and Parasara Samhita lay down expiatory ceremonies and injunctions for crimes against animals. Punishment was meted out in proportion to the degree of heinousness of the crime e. g. the blood of the killed cow was to be carefully examined and tested in order to ascertain whether she was lean or diseased when alive, as the nature of punishment varied according to the state of the cow’s health at the time of her death. Hence the testing was to be done very carefully.

When one is found guilty of carelessness in the treatment, the disease becomes intense, a fine or twice the cost of the treatment shall be imposed and when owing to defects in medicine, or not administering it the result becomes quite the reverse, a fine equal to the value of the animal shall be imposed. Every possible measure was taken by the state and the society for protecting their animals from thieves, carnivorous beasts, snakes, pythons, crocodiles and infectious diseases.

Different Referential Sources

In the Caraka Samhita, we find Veterinary science referred to in Siddhisthana verses.In Harita Samhita also we find the references about fever. It says that fever is an unrivaled diseases which affects all the creatures such as the horses, elephants, men, beasts, deer, buffaloes, asses, camels, forest trees, creepers, shrubs, mountains, serpents, birds and mice. This disease which is difficult of cure and destroys life is called fever in this world.

Similarity in Samhitas

The original Sailhotra-Samhita consists of 12000 verses. Salihotra made this treatise on horses consisting of 12000 verses. We also have the same number of verses in Agnivesa Samhita. The similarity does not end with the number of verses. Just as Ayurveda is divided into 8 sections, this science also has been Astanga i. e. divided into eight sections. The treatise of Salihotra gained currency due to its excellence and we find that Agni Purana quotes Salihotra, Matsya, Garuda Puranas and Hayayurveda also. This Salihotra-samhita has been translated into Persian, Arabic, Tibetan and English the Persian translation dating as early as 1387 A D. The fame of this work spread into the near East, that in Persian and Urdu the word Salotri stands for the horse doctor in their lexicons.

Samhitas on Different Animals

Samhita on Horses

The horse was a very useful animal in the wars and princes took pains to acquire mastery in the science. So the veterinary science was not just a subject for the professional practitioners. We have several instances of scions of royal dynasties who were famous for their learning in this field. King Nala was so well-versed in the science of horses that he earned the name of Asvavid. Nakula and Sahadeva, the twin sons of Madri, acquired the science from Drona Guru.

Palakapya Samhita

The medical authors attended equally to Elephants and cows besides horses . We have the Palakapya Samhita devoted solely to elephants. It is divided into 4 sections with 152 chapters in total. It comprises more than 10000 verses or 20000 lines and it is almost as big as Caraka Samhita. Such an elaborate treatise gives detailed information about the anatomy, surgery, physiology, pathology, major and minor diseases, diet and the drugs for elephants. We read in the descriptions of the wars of the ancient times that besides horses there were thousands of elephants on the battlefield and that was how the whole literature Hasti-Ayurveda came into existence.

Govaidyaka

Govaidyaka, treatment of the bovine species, is another branch of the veterinary science and this too has received full attention in Ayurveda. Similarly, goats and sheep, donkeys and camels, and even hawks were not neglected and we find special branches of treatises on these subjects.

The interdependence of human beings and animals with regards to the mutual welfare demands of us that we should take every possible care of animals in health and disease. With the ancients the animals were not merely useful, but also were treated in the same spirit as family members and well looked after. We should organize and establish efficient service centers to alleviate the ailment of animals. Present day Panjarapoles should be revived on scientific lines and thus fulfill the duty towards the civilization . This is the base of our ideal of Jiva-daya i. e. Compassion towards all the living creatures for which the country has always stood supreme.

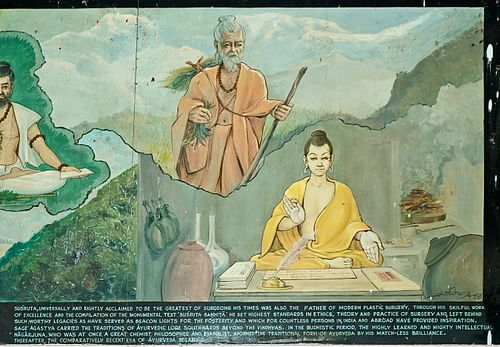

Sushruta: The father of surgery

The definition of an ideal surgeon according to the great surgeon Sushrutaa is “A person who possesses courage and presence of mind, a hand free from perspiration, tremor less grip of sharp and good instruments and who carries his operations to the success and advantage of his patient who has entrusted his life to the surgeon. The surgeon should respect this absolute surrender and treat his patient as his own son.”

Surgery forms a major role in general medical training. The ancient surgical science was known as Shalya Tantra. Shalya means broken arrow or a sharp part of a weapon and Tantra means maneuver. Shalya Tantra embraces all processes, aiming at the removal of factors responsible for producing pain or misery to the body or mind. Since warfare was common then, the injuries sustained led to the development of surgery as refined scientific skill.

All the four Vedas are in the form of Shlokas (hymns), verses, incantations, and rites in Sanskrit language. This treatise contains detailed descriptions of teachings and practice of the great ancient surgeon Sushruta and has considerable surgical knowledge of relevance even today.

The Rigveda – the earliest account of ancient Indian civilization – mentions that Ashwini Kumaras known as Dev Vaidya were the chief surgeons of Vedic periods, who had performed rare legendary surgical operations which included the first plastic surgery to re-join the head and trunk of saint Chyavana when Dakshya cut his head. Their other classic work included an eye operation of Reejashva, the implantation of teeth of Phushna in the toothless mouth, and the transplant of head of elephant on Ganesh whose head was cut by Lord Shiva. They transplanted an iron leg on Bispala – the wife of King Khela who lost her leg in war. Ashwini Kumaras had performed both homo- and hetro-transplantation during the very the ancient time of Rigveda which is estimated about 5000 years ago; such miraculous magical surgical skill of the Rigvedic period may seem mere legends or mystery to modern medical sciences. The surgical skill has traversed through the ages ranging from the Ashwini Kumaras, Chavana, Dhanvantari through Atereya Agnivesh and Shushruta. Craniotomy and brain surgery were also practiced in a more sophisticated way.

They do reflect some special surgical skills which laid down the foundation of Ayurveda – the fifth Indian Veda, the classical medical system of India. However, the realistic and systematic earliest compendium of medical science of India was compiled by Charak in Charak Samhita. It describes the work of ancient medical practitioners such as Acharya Atreya and Acharya Agnivesh of 800 BC and contains the Principle of Ayurveda. It remained the standard textbook of Ayurveda for almost for 2000 years. They were followed by Sushruta, a specialist in cosmetic, plastic, and dental surgery (Sandhan Karma around 600BC).

There are many Granthas and Samhitas dealing with Ayurveda; among them, Charak Samhita, Sushrutaa Samhita, and Ashtanga Sangraha are the three main pillars of Ayurveda. Charak Samhita and Ashtanga Samhita mainly deal with medicine knowledge while Sushrutaa Samhita deals mainly with surgical knowledge. Complicated surgeries such as cesarean, cataract, artificial limb, fractures, urinary stones plastic surgery, and procedures including per- and post-operative treatment along with complications written in Sushrutaa Samhita, which is considered to be a part of Atharva Veda, are surprisingly applicable even in the present time.

Sushruta is an adjective which means renowned. Sushruta is reverentially held in Hindu tradition to be a descendent of Dhanvantari, the mythological god of medicine or as one who received the knowledge from a discourse from Dhanvantari in Varanasi.[2] Sushruta lived 2000 years ago in the ancient city of Kashi, now known as Varanasi or Banaras in the northern part of India. Varanasi, on the bank of Ganga, is one of the holiest places in India and is also the home of Buddhism. Ayurveda is one of the oldest medical disciplines. The Sushrutaa Samhita is among the most important ancient medical treatises and is one of the fundamental texts of the medical tradition in India along with the Charak Samhita.

Sushruta is the father of surgery. If the history of science is traced back to its origin, it probably starts from an unmarked era of ancient time. Although the science of medicine and surgery has advanced by leaps and bounds today, many techniques practiced today have still been derived from the practices of the ancient Indian scholars.

Sushruta has described surgery under eight heads: Chedya (excision), Lekhya (scarification), Vedhya (puncturing), Esya (exploration), Ahrya (extraction), Vsraya (evacuation), and Sivya (suturing).

All the basic principles of surgery such as planning precision, hemostasis, and perfection find important places in Sushruta’s writings on the subject. He has described various reconstructive procedures for different types of defects.

His works are compiled as Sushrutaa Samhita. He describes 60 types of upkarma for treatment of wound, 120 surgical instruments and 300 surgical procedures, and classification of human surgeries in eight categories.

To Sushruta, health was not only a state of physical well-being but also mental, brought about and preserved by the maintenance of balanced humors, good nutrition, proper elimination of wastes, and a pleasant contented state of body and mind.

For successful surgery, Sushruta induced anesthesia using intoxicants such as wine and henbane (Cannabis indica).

He treated numerous cases of Nasa Sandhan (rhinoplasty), Oshtha Sandhan (lobuloplasty), Karna Sandhan (otoplasty). Even today, rhinoplasty described by Shushruta in 600 BC is referred to as the Indian flap and he is known as the originator of plastic surgery.

He described six varieties of accidental injuries encompassing all parts of the body. They are described below:

- Chinna – Complete severance of a part or whole of a limb

- Bhinna – Deep injury to some hollow region by a long piercing object

- Viddha Prana – Puncturing a structure without a hollow

- Kshata – Uneven injuries with signs of both Chinna and Bhinna, i.e., laceration

- Pichchita – Crushed injury due to a fall or blow

- Ghrsta – Superficial abrasion of the skin.

Besides trauma involving general surgery, Sushruta gives an in-depth account and a description of the treatment of 12 varieties of fracture and six types of dislocation. This continues to spellbind orthopedic surgeons even today. He mentions the principles of traction, manipulation, apposition, stabilization, and postoperative physiotherapy.

He also prescribed measures to induce growth of lost hair and removal of unwanted hair. He implored surgeons to achieve perfect healing which is characterized by the absence of any elevation, induration, swelling mass, and the return of normal coloring.

Plastic surgery and dental surgery were practiced in India even in ancient times. Students were properly trained on models. New students were expected to study for at least 6 years before starting their training. Before beginning the training, the students were required to take a solemn oath. He taught his surgical skills to his students on various experimental models. Incision on vegetables such as watermelon and cucumber, probing on worm-eaten woods, preceding present-day workshop by more than 2000 years are some instances of his experimental teachings. He was one of the first people in human history to suggest that a student of surgery should learn about human body and its organ by dissecting a dead body.

Sushrutaa Samhita remained preserved for many centuries exclusively in the Sanskrit language. In the eight century AD, Sushrutaa Samhita was translated into Arabic as “Kitab Shah Shun al –Hindi” and “Kitab – I – Susurud.” The first European translation of Sushrutaa Samhita was published by Hessler in Latin and in German by Muller in the early 19th century; the complete English literature was done by Kaviraj Kunja Lal Bhishagratna in the three volumes in 1907 at Calcutta.

Sushruta was also known as a medical authority in Tibetan literature.

Sushruta considered surgery the first and foremost branch of medicine and stated that surgery has the superior advantage of producing instantaneous effects by means of surgical instruments and appliances and hence is the highest in value of all the medical tantras. It is the eternal source of infinite piety, imports fame, and opens the gates of heaven to its votaries. It prolongs the duration of human existence on earth and helps human in successfully completing their missions and wearing a decent competence in life.

Sushruta (c. 7th or 6th century BCE) was a physician in ancient India known today as the “Father of Indian Medicine” and “Father of Plastic Surgery” for inventing and developing surgical procedures. His work on the subject, the Sushruta Samhita (Sushruta’s Compendium) is considered the oldest text in the world on plastic surgery and is highly regarded as one of the Great Trilogy of Ayurvedic Medicine; the other two being the Charaka Samhita, which preceded it, and the Astanga Hridaya, which followed it.

Ayurvedic Medicine is among the oldest medical systems in the world, dating back to the Vedic Period of India (c. 5000 BCE). The term Ayurveda translates as “life knowledge” or “life science” and is the practice of holistic healing which incorporates “standard” medical knowledge with spiritual concepts and herbal remedies in treatment as well as prevention of diseases. It was practiced in India for centuries before the Greek physician Hippocrates (c. 460 – c. 379 BCE), known as the Father of Medicine, was even born.

The Great Trilogy of Ayurvedic Medicine describes surgical procedures, diagnostic techniques, and treatments for various illnesses and injuries and even provides instructions for physicians on determining how long a patient will live (in the Charaka Samhita). The work of Sushruta standardized and established earlier knowledge through careful descriptions of how a physician should practice the art as well as specific procedures including performing plastic surgery reconstructions and the removal of cataracts.

The Astanga Hridaya combines the works of Charaka (c. 7th or 6th century BCE) and Sushruta, presenting a comprehensive text on both surgical and medical approaches to treatment, while also offering its own unique perspective. Sushruta’s work, however, offers the greatest insight into the medical arts of the three owing to the commentary he provides in-between or included in discussions of various ailments and treatment.

Sushruta the Physician

Little is known of Sushruta’s life as his work focuses on the application of medical techniques and does not include any details on who he was or where he came from. Even his birth-name is unknown as “Sushruta” is an epithet meaning “renowned”. He is usually dated to the 7th or 6th centuries BCE but could have lived and worked as early as 1000 BCE; although that seems unlikely as Charaka lived shortly before him or was a contemporary. He has been associated with the Sushruta mentioned in the Mahabharata, the son of the sage Visvamitra, but this claim is not accepted by most scholars.

SUSHRUTA SIGNIFICANTLY DEVELOPED DIFFERENT SURGICAL TECHNIQUES & INVENTED THE PRACTICE OF COSMETIC SURGERY.

All that is known for certain about him is that he practiced medicine in northern India around the region of modern-day Varanasi (Benares) by the banks of the Ganges River. He was regarded as a great healer and sage whose gifts were thought to have been given by the gods. According to legend, the gods passed their medical insight down to the sage Dhanvantari who taught it to his follower Divodasa, who then instructed Sushruta.

The practice of surgery was already long established in India by the time of Sushruta but in a less-advanced form than what he practiced. He significantly developed different surgical techniques (such as using the head of an ant to sew sutures) and, most notably, invented the practice of cosmetic surgery. His specialty was rhinoplasty, the reconstruction of the nose, and his book instructs others on exactly how a surgeon should proceed:

The portion of the nose to be covered should be first measured with a leaf. Then a piece of skin of the required size should be dissected from the living skin of the cheek and turned back to cover the nose keeping a small pedicle attached to the cheek. The part of the nose to which the skin is to be attached should be made raw by cutting the nasal stump with a knife. The physician then should place the skin on the nose and stitch the two parts swiftly, keeping the skin properly elevated by inserting two tubes of eranda (the castor-oil plant) in the position of the nostrils so that the new nose gets proper shape. The skin thus properly adjusted, it should then be sprinkled with a powder of liquorice, red sandal-wood, and barberry plant. Finally, it should be covered with cotton and clean sesame oil should be constantly applied. When the skin has united and granulated, if the nose is too short or too long, the middle of the flap should be divided and an endeavor made to enlarge or shorten it. (Sushruta Samhita, I.16)

Wine was used as an anesthetic and patients were encouraged to drink heavily before a procedure. When the patient was drunk to a point of insensibility, he or she was tied to a low-lying wooden table to prevent movement and the operation would begin with the surgeon sitting on a stool and tools on a nearby table. The use of wine led to the development of an anesthetic involving both alcohol and cannabis incense to either induce sleep or dull the senses to a stupor during procedures such as rhinoplasty.

Rhinoplasty was an especially important development in India because of the long-standing tradition of rhinotomy (amputation of the nose) as a form of punishment. Convicted criminals would often have their noses amputated to mark them as untrustworthy, but amputation was also frequently practiced on women accused of adultery – even if they were not proven guilty. Once branded in this fashion, an individual had to live with the stigma for the rest of his or her life. Reconstructive surgery, therefore, offered a hope of redemption and normalcy.

Sushruta attracted a number of disciples who were known as Saushrutas and were required to study for six years before they even began hands-on training in surgery. They began their studies by taking an oath to devote themselves to healing and to do no harm to others; very like the later Hippocratic Oath from Greece, which is still recited by doctors in the present day. After the students had been accepted by Sushruta, he would instruct them in surgical procedures by having them practice cutting on vegetables or dead animals to perfect the length and depth of an incision. Once students had proven themselves capable with vegetation, animal corpses, or with soft or rotting wood – and had carefully observed actual procedures on patients – they were then allowed to perform their own surgeries.

These students were trained by their master in every aspect of the medical arts, including anatomy. Since there was no prohibition on dissection of corpses, as there was in Europe for centuries, physicians could work on the dead in order to better understand how to help the living. Sushruta suggests placing the corpse in a cage (to protect it from animals) and immersing it in cold water, such as a running river or stream, and then checking on its decomposition in order to study the layers of the skin, musculature, and finally the arrangement of the internal organs and skeleton. As the body decomposed and became soft, the physician could learn a great deal about how each aspect functioned and how one could help a patient live a healthier life.

Sushruta on Medicine & Physicians

Sushruta wrote the Sushruta Samhita as an instruction manual for physicians to treat their patients holistically. Disease, he claimed (following the precepts of Charaka), was caused by imbalance in the body, and it was the physician’s duty to help others maintain balance or to restore it if it had been lost. To this end, anyone who was engaged in the practice of medicine had to be balanced themselves. Sushruta describes the ideal medical practitioner, focusing on a nurse, in this way:

That person alone is fit to nurse, or to attend the bedside of a patient, who is cool-headed and pleasant in his demeanor, does not speak ill of anyone, is strong and attentive to the requirements of the sick, and strictly and indefatigably follows the instructions of the physician.

The physician’s instructions should be followed without question because of the level of knowledge and expertise in application attained. A physician should always be focused on trying to prevent disease in the body, and this can only be accomplished if one understands how the body works in every aspect. To Sushruta, the practice of medicine was a journey of understanding for which a physician required a keen intelligence in order to recognize what was necessary for good health and how to apply that knowledge in any given situation. In one passage, he makes clear his purpose – or one of his purposes – in writing his compendium:

The science of medicine is as incomprehensible as the ocean. It cannot be fully described even in hundreds and thousands of verses. Dull people who are incapable of catching the real import of the science of reasoning would fail to acquire a proper insight into the science of medicine if dealt with elaborately in thousands of verses. The occult principles of the science of medicine, as explained in these pages, would therefore sprout and grow and bear good fruits only under the congenial heat of a medical genius. A learned and experienced medical man would therefore try to understand the occult principles herein inculcated with due caution and reference to other sciences. (XIX.15)

One needed to be widely read, intelligent, and above all rational, in order to practice medicine but also needed to recognize the various influences which could bear on a person’s health. Charaka had already emphasized the importance of understanding a patient’s environment and genetic markers in order to treat illness and Sushruta built upon this in encouraging his students to ask the patient questions and encourage honest answers. If a doctor could rule out environmental factors or lifestyle choices in a patient’s disease, then genetics could be considered. Sushruta, like Charaka, understood that a genetically transmitted disease might have nothing to do with the health of a patient’s parents but possibly with one or both grandparents.

If the disease was not genetic and had nothing to do with a patient’s environment, then it was most likely caused by one’s lifestyle, which had created an imbalance of the dosha (humors) of bile, phlegm, and air. Dosha were produced when the body acted on food that was eaten. A person’s diet, therefore, was considered of vital importance in maintaining health, and a vegetarian diet was encouraged. Sushruta suggests asking the patient dietary questions as well as others pertaining to exercise and even one’s thoughts and attitudes as these could also affect one’s health.

Sushruta recognized that optimal health could only be achieved through a harmony of the mind and body. This state could be maintained through proper nutrition, exercise, and rational, uplifting thought. In certain cases, however, when the patient’s imbalance was severe, surgery was considered the best course. To Sushruta, in fact, surgery was the highest good in medicine because it could produce the most positive results more quickly than other methods of treatment.

The Sushruta Samhita

The Sushruta Samhita devotes chapter after chapter to surgical techniques, listing over 300 surgical procedures and 120 surgical instruments in addition to the 1,120 diseases, injuries, conditions, and their treatments, and over 700 medicinal herbs and their application, taste, and efficacy, which are also dealt with in depth. It has been claimed by some scholars (such as Vigliani and Eaton) that surgery was a last resort in treatment as the ancients tried to avoid cutting into human bodies and explored other methods of healing far more often. Although there is some truth to parts of their claim, it does not apply to Sushruta. Surgery was not considered a last resort by Sushruta but actually the best means of alleviating suffering under certain conditions.

In a number of chapters throughout the book, a condition is described and a treatment suggested which includes details on how a physician should perform a certain surgery from start to finish. These details, in fact, are what marks the Sushruta Samhita as distinct from the earlier Charaka Samhita: Charaka established medical knowledge and practice while Sushruta developed surgical techniques and thus founded the practice known as Salya-tantra or “surgical science”.

According to the scholars S. Saraf and R. Parihar,The ancient surgical science was known as Salya-tantra. Salya-tantra embraces all processes aiming at the removal of factors responsible for producing pain or misery to the body or mind. Salya (salya-surgical instrument) denotes broken parts of an arrow/other sharp weapons while tantra denotes maneuver. The broken parts of the arrows or similar pointed weapons were regarded as the commonest and most dangerous objects causing wounds and requiring surgical treatment.

Sushruta has described surgery under eight heads: Chedya (excision), Lekhya (scarification), Vedhya (puncturing), Esya (exploration), Ahrya (extraction), Vsraya (evacuation) and Sivya (Suturing). All the basic principles of plastic surgery like planning, precision, haemostasis and perfection find an important place in Sushruta’s writings on this subject. Sushruta described various reconstructive methods or different types of defects like release of the skin for covering small defects, rotation of the flaps to make up for the partial loss and pedicle flaps for covering complete loss of skin from an area. (5)

These techniques were brought to bear on a variety of conditions ranging from plastic surgery reconstruction of the nose and cheek to hernia surgery, caesarian section birth, removal of the prostate, tooth extraction, cataract removal, treatment of wounds and internal bleeding, and many others. He further diagnosed and defined diseases of the eyes and ears, prescribed eye and ear drops, established the school of embryology, developed prosthetic limbs, and advanced knowledge of the human body through dissection and the resultant understanding of human anatomy.

Sushruta Samhita

His knowledge of how the body worked enabled him to heal without resorting to the supernatural explanation for disease or the use of charms or amulets in healing, but this is not to say that he discounted the power of a belief in higher powers. His commentaries throughout the book make clear that a physician should be aware of, and make use of, every facet of the human condition in order to treat a patient and maintain optimal health.

The Sushruta Samhita touches upon virtually every aspect of the medical arts but was unknown outside of India until around the 8th century CE when it was translated into Arabic by the Caliph Mansur (c. 753-774 CE). Even then, however, the text was unknown in the West until the late 19th century CE when the so-called Bower Manuscript was discovered which mentions Sushruta by name in a list of sages and also includes a version of the Charaka Samhita.

The Bower Manuscript is named for Hamilton Bower, the English army officer who purchased it in 1890 CE, and dates to between the 4th and 6th centuries CE. The existence of this text, written in Sanskrit on birch bark, suggests there may have been others – possibly many – which preserved the writings of Sushruta and other medical sages like him. Even before the discovery of the Bower Manuscript, however, British officials and soldiers in India in the 19th century CE had written home about startling surgical procedures, especially those of cosmetic surgery reconstruction, they had witnessed in the country. Their descriptions of these surgeries correspond closely with Sushruta’s instructions in his compendium.

An English translation of the Sushruta Samhita was not available until it was translated by the scholar Kaviraj Kunja Lal Bhishagratna in three volumes between 1907 and 1916 CE. By this time, of course, the world at large had accepted Hippocrates as the Father of Medicine and, further, Bhishagratna’s translation did not receive the kind of international attention it deserved. Sushruta’s name remained relatively unknown until fairly recently, as Ayurvedic medical practices have become more widely accepted, and he has begun to receive recognition for his enormous contribution to the field of medicine generally and surgical practice specifically.

Sushruta’s holistic view of healing, with an emphasis on the whole patient and not just on the symptoms presented, should be familiar to anyone in the modern day. Physicians today work up a medical history of a patient based on questions asked, research possible genetic causes for a problem, and prescribe treatments ranging from medical to surgical to so-called “alternative” practices. Further, a physician’s bedside manner in the modern day is considered important in establishing trust and encouraging the success of treatment. These practices and policies are considered innovations when compared with those as recent as the mid-20th century CE, but Sushruta had already implemented them over 2,000 years ago.

References

- Shalihotra on Wiki

- Pasu Ayurveda (Veterinary Medicine) in Garudapurāna by Subhose Varanasi & A Narayana

- Vet science dates back to ancient India—Hindustan Times

- Veterinary Science in Ancient India—Hindupedia

- Veterinary Medicine and Animal Keeping in Ancient India by R Somvanshi

- Veterinary Science in Ancient India—Innerworld.in

- The History of Veterinary Education in India by S Abdul Rahman

- Traditional veterinary medicine in India by G Mazars

- Selin H. Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures.Dordrecht: Springer Science+Business Media; 2015. pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Saraf S, Parihar R. Sushrutaa – The first plastic surgeon in 600 BC. Int J Plast Surg. 2006;4:2. [Google Scholar]