Successful Handling of Uterine Torsion and Its Management in Buffaloes

Uterine torsion in buffaloes more common form of dystocia, it can be defined as rotation of the pregnant uterine horn on its longitudinal axis (Purohit, 2011 a). Incidence of uterine torsion ranges from 52-70%, and its affects bovines mostly towards terminal gestation (Murthy et al., 1999), at parturition (Matharu and Prabhakar, 2001). Specifically at last first stage or early second stage of labour; or at post partum (Mathijisen and Putker, 1989). Uterine torsion is one of the complicated causes of maternal form of dystocia in bovines especially in buffaloes culminating in dead of foetus and/or dam if not treated early. Uterine torsion must be considered as an emergency, early presentation of cases to referral units and early institution of therapy gives favourable prognosis to the dam and foetal survival. Most of the time in field condition, veterinarian fails to diagnose the torsion cases; Accurate diagnosis of the direction of the torsion through per rectal examination is necessary prior to making attempts at rotation, as detorsion in the opposite or wrong direction will worsen the condition.

Torsion of uterus is a common form of maternal dystocia in bovines. Both maternal and fetal causes are attributed to the etiology of uterine torsion. The entire length of pregnant uterine horn rotates on its longitudinal axis to the left (anticlockwise) or right side (clockwise) along with uterine body, cervix and cranial vagina mostly. In severe cases of uterine torsion, there is vascular compromise to foetus resulting in death of fetus in utero. Since uterine torsion frequently occurs during parturition, there is twisting of birth canal so delivery of fetus cannot occur without external aids. Uterine torsion is a diagnostic dilemma for Veterinarians and a difficult obstetric procedure for less experienced persons. Prognosis and future fertility of dam depends on severity and duration of uterine torsion and methods of handling. Diagnostic evaluation of the condition continues to be transrectal palpation of the broad ligaments which rotate along with the rotating uterus. The success of management of the condition lies in the correct and timely diagnosis and early referral to referral centers.

What is Uterine Torsion?

By its more commonly known name, ‘twisted uterus’, this disease is fairly self-explanatory in terms of what the main problematic components are.

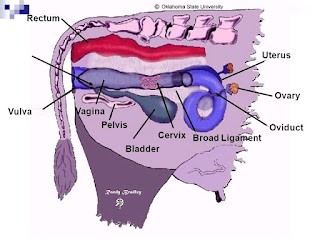

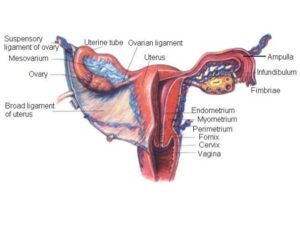

Animals that are part of the family Bovinae, including cattle, bison and buffalo, all share a similar ‘design flaw’ when it comes to the structure of their female reproductive organs. The uterus (more specifically, the uterine horns) are held in place by broad ligaments which provide dorsolateral support (i.e. they keep the uterus in a horizontal placement, up towards the spine of the animal). These ligaments are attached to the ventral side of the uterus (i.e. attaching to the uterus on the under-side).

In non-pregnant animals, this is a perfectly stable structure as the uterus is harbouring no extra weight and is situated in a fairly non-mobile position within the body cavity. However in pregnant cattle, as gestation advances, uterine contents grow, increasing the weight and size of the uterus; the broad ligaments do not extend proportionately, leading to instability of the uterus. Furthermore, the gravid (pregnant) uterus is positioned beyond the relatively stable area of attachment – instead, resting on the abdominal floor and being supported by the rumen, viscera and abdominal wall.

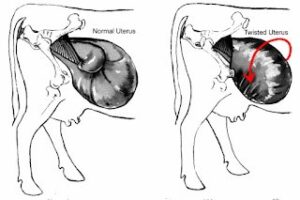

When instable, as is the case when the cow is in late stages of gestation, the uterus is at its most susceptible to being twisted. As a result of aggression from another cow, slipping over, turning quickly round corners, standing up and sitting down overly frequently or simply the myometrial contractions of the womb at the onset of parturition, the uterus can become ‘twisted’. What this actually means is that at a point along the birth canal, the uterus (and possibly some vaginal wall and cervix) has rotated around a point, to create a twist in the birth canal – this essentially halts any stages of labor from progressing.

The twist can be anywhere between a 45 degree angle up to 360 degrees. The larger the degree of twist, the more difficult the correction of the twist is. The twist direction can be anti-clockwise (left) or clockwise (right). Illustrated by the images below, where the red circle represents the uterus and the black dotted line represents the normal horizontal plane of the uterus.

If the twist was 360 degrees, the birth canal becomes almost impossible to fit through. The image below shows the normal birth canal (left) and the birth canal with a 360 degree twist, the blue lines representing the birth canal walls.

The foetus and its membranes also rotate with the uterus, meaning that there is a compression of blood supply to the foetus in the womb – death is often the case if intervention is not fairly prompt.

When the uterus twists, the broad ligaments also change positioning. This makes it possible to diagnose uterine torsion by rectal examination, palpating the broad ligaments to determine their position.

The point of torsion can be at several points along the birth canal. From the perspective of the calf, it can be before the cervix (pre-cervical torsion) or after the cervix (post-cervical torsion). Post cervical torsions are often more easier to diagnose visibly as more of the vaginal wall tissue and vulval lips are involved – showing signs of tension and a characteristic ‘corkscrew’ effect in the tissue of the vaginal wall, getting tighter towards the point of torsion.

The direction of the twist can (and must be) identified by the twisting in the vaginal wall. If the vaginal wall is corkscrewing to the left, then the uterus has twisted to the left, when viewing the cow from behind. Correction would therefore involve twisting the uterus to the right to oppose the initial twist.

Uterine torsion essentially creates a blockage in the birth canal. In twists greater than 90 degrees, it is rare that the water bag can pass through, meaning that often, first stage labor is noted but the progression to stage 2 is extremely slow or in fact non-existent. Torsions occur just before stage 1, during stage 1 or at initiation of stage 2 of labor.

As these twists most commonly occur just before the onset of labour or during labour, an important factor of cattle behaviour, which may well have an important role in torsion, must be noted – alternating between lying down and standing. Cattle stand up from a recumbent position first by getting up onto their hind legs, leaving their fore legs kneeling on the ground. This means that their hind quarters are in the air, in a downward trajectory.

Although this is not a problem in non-pregnant cows, as mentioned before the gravid uterus of pregnant cattle is carrying significantly more weight. When the hind quarters are raised in the air as shown by the illustration above, the gravid uterus is essentially hanging in the abdominal cavity, pushing forwards on the abdominal wall and almost hanging with a vertical axis (instead of a longitudinal axis), which makes it more likely that the uterus will twist due to the vertical angle at which the uterus is hanging, especially if a slip of fall occurs as the cow is getting up. The red line above represents the axis that the uterus will have, compared to the yellow line which is the axis the uterus should have when the cow is lying flat (which is most stable) and the blue circle shows the area in which the uterus is suspended within. So instead of being flat and stable, if the cow is frequently getting up and lying down, there is an increased chance of the uterus twisting. Alternating between lying and standing is a common behaviour for a cow that is about to calve so essentially at this time the cow is at the most risk. In light of this it is of vital importance to ensure that the environment of the cow at this point is safe – i.e. the chances of the cow slipping, falling or being pushed by other cows, is minimal.

Uterine torsion occurs most commonly in stage 1 of labor or onset of stage 2 of labor. Often it is recognised by failure of the cow/heifer to progress in calving. Due to the obstruction in the birth canal caused by the twist, it is unlikely that the any fluids are expelled and palpation of the calf is more difficult. Cows will often hold out their tail/tailhead and act more restless. The vulval lips are sometimes tight or skewed in cases of strong twists and the vaginal walls are much drier than they should be at stage 1/2 of labor.

It is therefore important to recognise and take note of when a cow is entering into first stage of labor. The most difficult and severe cases of uterine torsion are those that have been left too long before seeking veterinary assistance – in other words, the stockman has not recognised the delay in progression. Although delays can be common and not disease related, the time taken to check the dilation of the cervix or check for a twisted uterus is much less than the time, effort and cost of a severe uterine torsion case.

Pertaining to the original statement of buffalo being more susceptible than cows now, using the information given so far, this can be explained. Buffalo nowadays have a very weak musculature of broad ligaments, as well as an extremely ‘deep’ abdomen compared to cows – therefore, combining these predisposing anatomical factors (i.e. the weak musculature, deep abdominal cavity and the poor bovinae broad ligament structure) this makes buffalo the most susceptible to uterine torsion compared to any other species.

Predisposing factors

Uterine torsion is more common in buffalo and cow than other domestic species. Incidence is noted to be highest in dairy cows and only rarely seen in beef cows (Frazer et al., 1996). Bos indicus cattle are stated to be the lowest risk group of cattle which may be due to the fact that insertion of broad ligament in these breeds change from ventral to dorsal position as it runs along the uterine body, allowing the uterus little freedom to move within the abdomen (Sloss and Dufty, 1980). Pluriparous animals are at a higher risk, possibly due to decrease in uterine and mesometrial tone is caused by multiple birth. A geographic association has also been recognized regarding the incidence of uterine torsion (Roberts, 1986).

Etiology

A number of theories have been promulgated for explaining the predisposition of bovine uterus to torsion, however maternal and fetal destabilizing factors behind occurrence of uterine torsion are not well understood (Ghuman, 2010). The main predisposing cause contributing to development of uterine torsion is thought to be unstable anatomical arrangement of bovine uterus which include 1) sub-ilial attachment of broad ligament 2) broad ligaments being attached along the lesser curvature of uterus, thus leaving greater curvature free 3) uterine horns not fixed by broad ligament and lying free 4) relatively small increase in length of broad ligament but the pregnant horn extends massively beyond area of attachment in advanced pregnancy (Ghuman, 2010). Higher incidence of uterine torsion in buffalo than cattle is partly due to big length of broad ligament in buffaloes which make pregnant uterus less stable. Weak musculature of broad ligament, lack of tonicity in broad ligament in pluriparous animals and enlargement of pregnant uterine horns are among other anatomical predisposition causes of uterine torsion. Unfilled rumen, capacious and pendulous abdomen seems to facilitate easy rotation of pregnant uterus in buffaloes compared to cattle and in pluriparous buffaloes compared to primiparous (Singh, 1991). Other factors include hilly terrain, slipping, sudden movement of dam, unsteady walk, while lying down bovines go down on forelegs first and while getting up, the hindquarters are elevated first, thus each times, the pregnant uterus is temporarily suspended in the abdominal cavity and is prone to torsion (Drost, 2007). Energetic movements of fetus during first stage labor, lack of fetal fluids and reduced rumen volume prior to parturition (Drost, 2007).

Clinical signs

The usual clinical signs are the onset of labor without delivery of fetus and/or fetal membranes and later regression of parturition signs (Singh et al., 1979). The animal may show signs of mild discomfort. The animal may adopt a rocking horse stance and show mild colic pain and constipation. Partial anorexia, dullness and depression may be evident (Ali et al., 2011). Restlessness and arching of back and colic may be seen in some buffaloes (Murty et al., 1999). In postcervical uterine torsion one or both lips of the vulva are pulled in because of rotation of the entire birth canal. Vaginal examination reveals twisting of the vaginal mucous membranes and the hand cannot be passed deeper into the anterior vagina which has a conical end in torsion with a degree of 180° or more. In lesser degree torsions however, the fetus can sometimes be felt. The direction of the vaginal fold twisting is considered the evidence for the direction of torsion. On rectal examination, the twisted uterine horn can be felt and the broad ligament on the side of torsion is rotated downwards sometimes palpable under the uterus and the ligament on the opposite side is tense and stretched and crossing to the opposite side (Purohit et al., 2011a). The positive diagnosis of uterine torsion should thus, be based on the location of broad ligaments palpated per rectum. Animals at many locations may be presented to the obstetrician after varying times since the first onset of labour; hence, the clinical signs of shock and toxaemia may be evident depending upon the severity of torsion, previous handling, death of fetus and posttorsion complications.

Clinical diagnosis

Tentative diagnosis arrived at based on history and clinical signs. Moreover definitive diagnosis made by either per vaginal or per rectal examination or both.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS:

Uterine torsion often shares clinical signs with other clinical conditions likes, simple indigestion, rumen impaction, intestinal volvulous, intestinal torsion, intussusceptions, left displacement of abomasum, acidosis, traumatic reticulo pericarditis (TRP), broncopneumonia, vagal indigestion, diaphragmatic hernia (DH). Moreover delayed cases of uterine torsion have 90-95 % of similar clinical signs with other medical-surgical condition. Best differential diagnosis method for uterine torsion from other clinical condition is Per rectal and per vaginal examination.

Based on history and clinical signs

Tentative diagnosis is easy when the typical abnormal symptoms appears at the time of parturition or last trimester of gestation. Typical history of uterine torsion will indicate that animal with completed gestation, engorged teat with let down of milk and relaxation of pelvic ligaments, no rupture of the allantoic /amniotic water bags nor the appearance of fetus from the vulvar lips (Prabhakar et al., 1995).

General and systemic signs

Tachycardia, increased respiratory rate with oral breathing, restlessness, frequently lie down and gets up, severe abdominal pain (Colic) with kicking of the abdomen with her hind legs on the side of the pain (Noakes et al., 2001). Severe abdominal pain may suggestive of stretching of the broad ligaments from their normal anatomical position (Sloss and Dufty, 1980). Moreover increase in abdominal straining due to stimulation of stretch receptors present in the vaginal walls. If torsion cases untreated for several days, gradually the appetite decrease, rumen function ceases and faeces become hard (Srinivas et al., 2007).

External sign

Displacement of upper vulval commissure inward towards right or left side in accordance to side of uterine torsion. Vulval oedema with necrosis of vulvar mucosa due to compression/ strangulation of vaginal vein and lymphatic drainage, and a mild to moderate depression of lumbo-sacral vertebrae are not the valid features in all cases (Schonfelder et al., 2003).

Per vaginal examination

Most probably post and pre cervical torsion can be diagnosed by vaginal examination; however per rectal examination is indicated for confirmative diagnosis of pre cervical torsion.

Post-cervical uterine torsion

In normal pregnant animal, per vaginally no vaginal folds is palpable and flower like external os of the cervix easily accessible. In case of torsion vaginal folds are palpable due to rotation of cervical area of broad ligaments. Post cervical torsion can be easily diagnosed by per vaginal examination. In buffalo concern post cervical torsion was common. About 69-96 % uterine torsion are post cervical in which the broad ligaments twist up to caudal to the cervix and involves rotation of anterior portion of vagina (Noakes et al., 2001). During vaginal examination, spiral folds or twists are present in vaginal wall along an reachable cervix indicative of post cervical with less than 180° torsion (Noakes et al., 2001; Drost, 2007). Spiral folds or twists are present in the vaginal wall with not accessible cervix indicative of post cervical with more than 180° torsion.

Pre-cervical uterine torsion

In pre cervical torsion, the twisting of broad ligaments lies on the body of uterus and does not include the cervix, so, during per vaginal examination vaginal folds are absent and cervix is easily reachable (Noakes et al., 2001)

Pre and post cervical torsion

Rarely clinically presented cases on per vaginal examination reveals vaginal fold with easy accessible cervix; however on per rectal examination reveals twisting of broad ligaments over the body of the uterus also.

Per rectal examination

In normal pregnant animal, the course of the broad ligaments palpated on the side of the uterus, where as in pre and post cervical torsion the orientation of broad ligaments is altered from their normal anatomical position and these can be felt by twisted uterus (Noakes et al., 2001). However direction of uterine torsion can be diagnosed by per rectal examination. Per rectal examination validate for both pre and post cervical torsion. The Clinical Diagnosis of Uterine Torsion in Bovines: An Update 964 direction of torsion may be of Right side (Clock wise) or Left side (Counter Clock wise) (Roberts, 2004) Right side broad ligament rotated along with uterus and pulled vertically downwards beneath the uterus, whereas left side broad ligament is tightly stretched above the uterus in right side torsion. Vice-versa for left side torsion. The examiners hand will move in a pouch like structure formed by crossing over of broad ligaments (Berchtold and Rusch, 1993; Noakes et al., 2001; Drost, 2007).

Palpation of middle uterine artery

Right and left middle uterine artery supplying blood to the uterus and its structure. It increases in diameter as pregnancy advances. Normally in pregnancy right middle uterine artery governs main function than left middle uterine artery due to right horn pregnancy in bovines. It normally goes along with course of broad ligaments over the shaft of ilium. Cranial displacement of right and left middle uterine artery on the right and left side of the uterine torsion respectively, it may be due to stretching of broad ligaments (personal observation).

Palpation of foetus

At term normally foetal parts like head and foetal limbs can be easily palpable per rectally. Moreover per vaginally head and limbs with movement of foetus while pinching of foetal limbs over the cranial vaginal wall. In torsion cases palpation of foetal parts is difficult due to stretching of broad ligaments and ventrally displaced uterus with foetus; Moreover after detorsion foetal parts like head and limbs are palpable through per rectal examination (personal observation) that indication of detorsion occur.

Fore arm entrance test

At term per vaginal examination of normal pregnant animal allows three fourth of the fore arm to reach the cervix where as in torsion allows one fourth of the fore arm due to obstruction by vaginal folds. However it may vary from parity of animal and hand size of the obstetrician (Personal observation).

Finger side test/ method

Vaginal folds are not allowing the hands but allows the fingers. However through the vaginal folds, fingers go to the left side and dorsal face of the fore arm (hand) faced on right side of the animal indicative of Right side torsion. Vice-versa for Left side torsion. But, this method not valid for pre cervical torsion and adhesion formed cases. Moreover it can be confirmed by per rectal examination (Personal observation).

Treatment

Choice of treatment will depend upon experience of Veterinarian, severity of torsion and condition of dam.

Per-vaginal foetal rotation

It depends upon degree of torsion and amount of cervical dilatation (Sloss and Dufty, 1980). With rotation of 900, the fetus can be easily rotated manually into a normal dorso-sacral position (Drost, 2007). If torsion is in the range of 90-1800 and cervix is dilated then this is the method of choice with rolling of dam being the next (Morten and Cox, 1968).

Rolling of dam

Rolling is indicated if dam is recumbent and the fetus is not approachable due to severity of torsion or if torsion has occurred before expected time of parturition (Roberts, 1986). Before rolling, stabilization of dam is necessary with fluids and lifesaving corticosteroids. Rolling can be done with or without plank with varying degree of success. However, success rate is high when using plank (12 feet long and 10 inch wide) is placed on the upper paralumbar fossa. In Schaffer’s method, principle is to rotate dam to same degree and direction to which the uterus has rotated, keeping the fetus fixed by fixing uterus with a plank (Schaffer, 1946). In brief, after ascertaining the side of torsion, animal is casted carefully in lateral recumbency on the side of direction of torsion and front and hind limbs are secured separately. The plank is placed on upper paralumbar fossa of dam in an inclined manner with lower end on ground. Next step is to slowly roll over the dam on its back. At the same time, an assistant stands on the plank to modulate pressure first on the left side (when animal is casted on right side), followed by ventral abdomen and lastly on right side. After each roll, effectiveness of roll is judged by vaginal or rectal examination (Ghuman, 2010). However thick skin of buffaloes causes skidding of the plank at the time of rolling. Moreover, pendulous abdomen of buffalo warrants greater pressure for fixation of pregnant uterus. For this, Sharma’s modified Schaffer method is used which include change in dimension of plank (length 11.9 feet, width 9 inch and 2 inch thickness), while rolling plank is anchored by 1-2 assistant, an additional assistant modulate the pressure on the plank by pressing upper end of plank and buffalo is rolled quickly (Singh and Nanda, 1996). It is suggested that if torsion is not relieved after 3 rolls then failure should be admitted and surgery is indicated (Nanda et al., 1991).

Caesarean section

Most uterine torsions do not warrant surgical intervention and caesarean section is never performed as the first choice. Delayed uterine torsion (>72 hours) should be directly subjected to caesarean operation in order to avoid undue stress of rolling. Animal with a friable, septic uterus containing an emphysematous fetus is a poor candidate for abdominal surgery (Amer et al., 2008). While attempting caesarean, the cost of operation and value of the animal should be judiciously considered (Ghuman, 2010).

Compiled & Shared by- Team, LITD (Livestock Institute of Training & Development)

Image-Courtesy-Google

Reference-On Request.