Switching to Cage- free Poultry farming: A Revolution in Poultry Farming & The future source of Egg and Chicken Meat under fast changing climatic scenario

Cage-free revolution is new era of layer farming.Ever since the poultry revolution of the mid 80s uplifted the humble egg and crowned it as a cheap-yet-stellar source of protein, India has harboured a growing affair with eggs.

Costing as little as Rs 3 per egg and available at every corner shop, they are a convenient and cost effective way of bringing some balance to our carbohydrate-heavy diets. But are they extorting a far heavier price from the birds that produce them.

History of cage free

Ruth Harrison was a British animal welfare activist and author. In 1964 she published Animal Machines, in which she describes the intensive poultry and livestock farming. In reaction of this book, the UK government installed a research commission, led by Professor Roger Brambell. The research was into the welfare of intensively farmed animals. The commission formulated recommendation, which became known as Brambell’s Five Freedoms, to describe the needs of a animal related to welfare. As a result of the report, the Farm Animal Welfare Advisory Committee was created to monitor the livestock production sector. This lasted in a list with the five freedoms.

The Five Freedoms have been adopted by professional groups including veterinarians and several organizations.

- Freedom from hunger or thirstby giving access to fresh water and a diet to maintain full health and vigor.

- Freedom from discomfortby providing an appropriate environment including shelter and a comfortable resting area.

- Freedom from pain, injury or diseaseby prevention or rapid diagnosis and treatment.

- Freedom to express (most) normal behaviourby providing sufficient space, proper facilities and company of the animal’s own kind.

- Freedom from fear and distressby ensuring conditions and treatment which avoid mental suffering.

During the period between 1980-2000, there was almost no scientific knowledge about animal welfare available. Animal Welfare mainly focused on fighting against excesses. There were mainly large public campaigns against for example, crates for calves. In the council of Europe, codes of conduct were developed. These codes of conduct only could be adopted by uniformity. This leads to a lot of discussion and a minimum of legislation.

Due to some disease outbreaks like foot and mouth disease, a public debate about intensive farming emerged. In the past farmers produced food, but this production model made a 180 degrees turn. The market no longer dictated the sector. The market became more consumer oriented. Farmers had to produce wat consumers asked for.

In the period from 2010 until nowadays, we focus more on innovation and sustainable products. Food safety, effects on the environment, and animal health are topica that have become very important. Banning outbreaks of salmonella, campylobacter, etc., reduce energy, dust, etc. and reduce the antibiotic use, to prevent antibiotic resistance. New concept were born that have taken these subject and animal welfare into account. For laying hens Vencomatic has the Rondeel concept, where food safety, sustainability, animal health and animal welfare are key. For broilers there is the on farm hatching X-treck system of Vencomatic.

Due to this development more and more eggs were requested from aviary systems instead of cages. Different non-government groups forced the government to give the birds more freedom. This resulted in a cage ban in 2012 announced by the government in Europe. So, the cage ban in Europe was forced by the government, not by the industry and this had an effect. Since September 2019 in The Netherlands there is also a debeaking ban. We think more countries will follow this example.

The world of keeping laying hens is changing fast. After Europe, other countries are thinking to move or are already moving to animal welfare friendly systems. This process lasted 40 years in the Netherlands, but goes much more rapid all over the world. In the UK, free-range systems are the most popular of the non-cage alternatives, accounting for around 50% of all eggs produced, compared to 4% in barns and 3% organic. But so far most of the layers worldwide are still in cages. Apart from Europa, there is another movement in the cage free direction. American companies, like Starbucks, Mc Donalds, Unilever, public announce that they only want to use cage free eggs in the future. How could this happen? The request for cage free eggs comes from welfare organizations, Non-government organizations, and by large multinational companies. But most important, consumers are moving and the market requests more and more cage free eggs, now and in the future. For example the big company Unilever announces to be fully cage free in 2020 worldwide.

Welfare and cage free

Historically, animal welfare has been defined by the absence of negative states such as disease, hunger and thirst (Bracke and Hopster, 2006). However, a shift in animal welfare science has led to the understanding that good animal welfare cannot be achieved without the experience of positive states (Hemsworth et al., 2015). Unequivocally, the housing environment has significant impacts on animal welfare. Cage and Cage-free housing systems have impact on some of the key welfare issues for layer hens: musculoskeletal health, disease, severe feather pecking, and behavioural expression.

Birds can have bone fragility and muscle weakness when they are unable to move and exercise sufficiently (Webster, 2004). This happens in conventional cages, where birds have extreme behavioural restriction. Therefore, they often suffer from osteoporosis (LayWel, 2006). Of all housing systems, hens in conventional cages suffer the poorest bone strength, and the highest rate of fractures at depopulation (Widowski et al., 2013). In cage-free systems, the hens have the best musculoskeletal health (Rodenburg et al., 2008). A study by Rodenburg et al. (2008) comparing cage-free and furnished cages found that hens in cage-free systems had stronger wing and keel bones than hens in furnished cages. An increased behavioural repertoire and the ability to exercise, including walking, running, perching, wing-flapping, and flying increases musculoskeletal strength, and decreases the incidence of osteoporosis and fractures which occur during depopulation.

Looking at disease, the incidence of bacterial infections, viral diseases, coccidiosis, and red mites in litter-based and free-range systems are higher than in cage systems (Rodenburg et al., 2008; Fossum et al., 2009; Widowski et al., 2013). However, with the correct biosecurity and vaccination programmes, the risk of these incidences will decrease (Martin, 2011; Fraser et al., 2013). Hens in conventional cages may experience metabolic disorders due to lack of exercise. Caged hens can show ‘cage layer fatigue’ which is due to bone weakness, fractures of the thoracic vertebrae, and compression of the spinal cord (Duncan, 2001). Other non-infectious diseases including fatty litter and disuse osteoporosis are more prevalent in conventional cages compared with systems that allow greater opportunities for behavioural expression and movement (Weitzenbürger et al., 2005; Kaufman-Bart, 2009; Lay et al., 2011; Widowski et al., 2013). Fatty liver is a metabolic disease typically seen in conventional cages (EFSA, 2005; Jiang et al., 2014) which can cause rupture of the liver and sudden death. The main factors which are thought to contribute to the development of fatty liver include lack of exercise and restricted locomotion, high environmental temperatures, and a high level of stress (EFSA, 2005).

Feather pecking and cannibalism occurs in all types of housing systems (Bestman et al., 2009). Housing birds in large groups can cause an increased risk of severe feather pecking (Potzsch et al., 2001). However, Management practices that may minimise the risk of severe feather pecking are the provision of adequate nutrition, appropriate feed form, high-fibre diets, suitable litter from an early age onwards, no sudden changes in diet or environmental conditions, minimising stress and fear in the birds, provision of environmental enrichment, appropriate rearing conditions, good husbandry and matching the rearing and laying environments (Kjaer and Bessei, 2013; Rodenburg et al., 2013; Hartcher et al., 2016). Furthermore, feather pecking is heritable (Savory, 1995; Kjaer and Bessei, 2013; Bessei and Kjaer, 2015), and current studies are investigating traits which may predispose particular birds to initiate the behaviour, to enable genetic selection against these traits.

Welfare in cage-free systems is currently highly variable, and needs to be addressed by management practices, genetic selection, further research, and appropriate design and maintenance of the housing environment. Conventional cages lack adequate space for movement, and do not include features to allow behavioural expression. Hens therefore experience extreme behavioural restriction, musculoskeletal weakness and an inability to experience positive affective states. Furnished cages retain the benefits of conventional cages in terms of production efficiency and hygiene, and offer some benefits of cage-free systems in terms of an increased behavioural repertoire, but do not allow full behavioural expression (Hartcher and Jones, 2017). Housing systems for hens differ in the possibilities for hens to show species specific behaviors such as foraging, dust-bathing, perching and building or selecting a suitable nest. If hens cannot perform such high priority behaviour, this may result in significant frustration, or deprivation or injury, which is detrimental to their welfare (Fraser et al., 2013).

Hens should be provided with sufficient space to allow the movements described above to be carried out by each bird taking into account the presence of other birds and the frequencies of exercise and other activities required by the birds to avoid significant frustration, or deprivation or injury. Injurious pecking should be minimized by appropriate housing and management as well as by genetic selection. Wherever possible, this should be achieved by provision for the hens’ needs, including opportunities to avoid birds which carry out the pecking, rather than by beak-trimming.

A System of Suffering

India’s demand for eggs has grown exponentially in the last decade. According to a poultry sector review conducted by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation in 2008, India was the third largest producer of eggs per annum, a majority of which is consumed domestically.

As a result, egg production has been transformed from a backyard activity for rural farmers to a highly organised urban industry. To maximise production, companies follow an intensive system of breeding hens indoors in factory settings.

Instead of foraging for food, as they would in a free range setting, commercially bred high-yield hens spend their entire lives cooped up in wire battery cages. Several thousand hens are packed into small cages, which afford them “less living space than an A4 sheet of paper”, according to Nuggehalli Jayasimha, campaign manager with Humans Society International, an NGO working in the field of animal rights. The cages are placed in rows, side by side and stacked several tiers high.

From birth until they are 18 to 22 months old, female birds lay an average of 250 to 300 eggs a year. At the end of two and a half years, when their tightly monitored egg production begins to drop, the birds are culled and fresh chicks take their place.

Although, 60% of the eggs in the world still come from industrial farms, many countries, including Switzerland, Belgium, Sweden, Germany and Australia have banned battery . cages. The European Union will phase them out by 2012. But India has been slow to catch on to the global trend. Even though the rural poultry sector still contributes significantly to the total national egg production, these desi eggs don’t reach urban consumers because there are few cooperatives of rural egg farmers.

There are only a handful of urban agriculturists in the country who have set up free range farms. Out of these, only a couple have the marketing muscle to stock their products on the retail shelf, which means that the availability of free range eggs is spotty at best, even in urban areas.

Until ten or fifteen years ago, in most countries the vast majority of table eggs were produced in cage systems because they best addressed a number of critical issues:

- Large numbers of birds per shed, saving land and capital resources

- Cheap quality food for the generation recovering from World War 2

- Easy egg collection by automatic conveyor belt

- Mass production was regarded as progressive and efficient

At that time, non-cage systems were generally not automated, so that eggs were collected by hand, making them very expensive and restricting the size of operation.

In the past, only keen green animal welfare activists consumed free-range eggs (the barn concept did not yet exist) and were willing to pay double or more for them. This high-end niche market was served by small independent free-range farmers.

Market change

This reality has dramatically changed and by 2020 cage-free eggs became much more dominant, representing the majority of eggs produced (in the UK, the EU, Australia), or at least mainstreamed (in the USA).

Division of eggs produced in 2020

| Country | Cage | Free range | Barn | Total cage free |

| UK | 42% | 56% | 2% | 58% |

| Europe | 48% | 18% | 34% | 52% |

| USA | 70% | 30% | ||

| Australia | 43% | 47% | 10% | 57% |

Each country has its own standards for defining the different categories: organic, free range and barn, based on the amount of space provided per bird and sometimes the shed size, equipment profile, access to outside, etc.

Over the last decade, hundreds of companies around the world have committed to source cage-free eggs by 2025 or earlier. Commitments sometimes result from conversation with groups advocating to improve the treatment of animals, as cage-free housing is widely believed to provide better welfare for egg-laying hens. When conversation does not work, advocacy groups may run a campaign of public pressure, including protests or shaming in the media, which usually leads to a commitment.

Many companies across the world are moving towards cage-free chicken farms and India should not be left behind. Chickens are universally scientifically accepted as a sentient being, able to experience and feel pain, pleasure, comfort, stress, thirst, hunger and fear similar to a ‘pet’ cat or dog. Domestic chickens are said to have the same cognitive abilities equal to a seven-year-old child in terms of some aspects of memory. The modern egg and meat chicken is derived from the Asian jungle fowl. Yet despite many thousands of years of domestication and selective breeding, these birds retain behavioural needs of their ancestors, such as foraging, perching, dust bathing and where relevant, nesting. Cage production fails to meet these basic needs, which also have production implications. Egg layer cages (often called battery cages) don’t even provide a nesting box and have been banned in many countries, while meat chicken cages are prohibited in most major poultry markets. The issue of poultry cages is coming home to roost in Asia, with the proposed ban on cages in India. Layer hen cages have been well established to be detrimental to hen welfare restricting movement and prohibiting all necessary behaviours including nesting (preparing a nest, an important pre-emptive egg-laying behaviour which serves to trigger hormones for egg laying). The scientific evidence is clear that the estimated 200 million layer hens in India would be better served by cage-free systems. “Birds in cages cannot adequately exercise, forage, perch, dust bathe, escape or avoid aversive interactions. They are also more fearful than birds in large group housing systems. The impacts of behavioural restriction also have a welfare and production impact, also relating to foodborne diseases such as Salmonella and other public health concerns,” said Gajender K Sharma, India Country Director at World Animal Protection. In the coming year Indian Poultry industry face another change with cage fee poultry. Our govt also very concern to implement the cage free poultry in India as soon as possible.

The progression towards cage free-was motivated by a number of related factors:

- Concern for animal welfare.Gradually, there has been increased concern for animal welfare in general and the term “animal rights” has been coined. This includes all sorts of animals, including domestic pets, farm animals and wild animals.

- Wealthier consumers.In the post-war era, the first priority was to provide for the population. Egg rationing (one egg per person per week) was only abolished in the UK in 1954. As living standards improved, consumers looked for improved quality. For many consumers, if an egg had been produced in a humane way it was part of its quality.

- Public concern, which translated into a market opportunity, gradually incentivised poultry equipment companies to develop products that made mass production of cage eggs possible. Thus, the costs of producing cage-free eggs declined, becoming much closer to the cost of cage eggs.

- Concern for animal welfare is on a scale.Few people would pay triple or even double for free-range or cage-free eggs. If the price of cage-free were identical to cage eggs, almost everybody would eat cage-free.

As the millennial generation has higher awareness of bird welfare, increased demand has led to an increase in production and to the adoption of economies of scale, thus lowering production costs.

Enriched cages

The first large-scale break with the traditional cage system was in Europe when the European Union looked for technological solutions that could balance between bird welfare and production cost. The system they found was the “colony system” or “enriched cages.”

Larger cages housed around one hundred birds instead of six–seven hundred. Each bird had more room to live, as well as a scratching area (artificial grass), toys and a private cell in which to lay its eggs. Regulations to enforce compliance with this system were passed so that by around 2015 it had completely replaced battery cages. This change cost European growers and taxpayers billions of euros.

The system was technically a massive improvement compared to battery cages. The fundamental mistake, however, was that the EU used a top-down approach. While the EU Council decided on the solution that consumers would prefer, consumers still saw the enriched cages or colonies as “cages” and showed a reluctance to buy these eggs. The unfortunate result was a waste of billions of euros in investment by the European poultry industry and the taxpayer and, within several years farms were forced to return to barn or free-range to meet consumer demands.

This is a great lesson in the limits of regulation and government guidance. Regulations can ensure safety, a level playing field and more, but they cannot dictate to consumers what they want to buy and what level of animal welfare they will find acceptable.

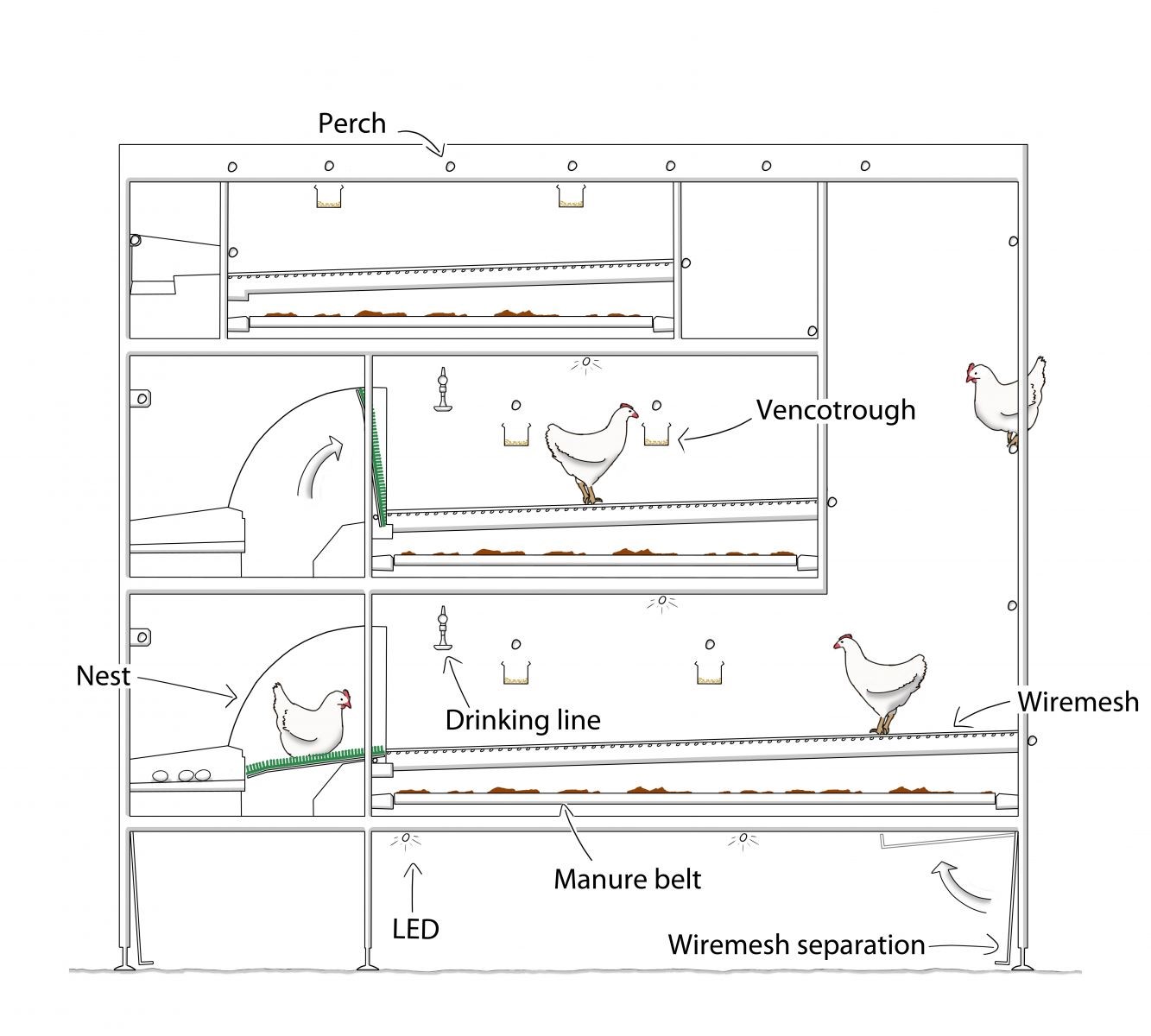

Nesting systems a game changer

The introduction of automatic nests was a major breakthrough as it enabled the production of cage-free eggs at reasonable and competitive prices. Hens can now lay eggs in nests, which are then transported automatically to a central collection point.

An automatic nesting system quickly became the key element in each barn or cage-free shed. It eliminates the expensive and labour-intensive need to collect eggs manually; if the eggs remain in the nest too long or, worse, remain on the floor, they will get dirty and lose freshness.

Hens still need to be trained to actually lay the eggs in the nesting system, but the training is becoming easier, and currently there are also some robotic systems that help train the birds to do that.

Free-range and barn sheds

In the “barn system,” the hens are free to move around the whole shed. A modern barn system will have various perches and conveyors spread out in a way that the hens can nest at different heights in the shed with no restriction. The birds move from level to level by flying (or at least enhanced umping).The shed is seen as a three-dimensional space that can be filled efficiently rather than just as a floor. Thus, more birds can be kept per square meter than in a floor-only barn, reducing capital costs.A free-range house is the same as a barn house, with the additional possibility for the birds to go outside, weather permitting. According to the regulatory regime, there will be limitations on the number of birds per meter and per shed.While each country or standard has different requirements for birds per square meter, access to outside, etc., the basic condition is that the birds can go outside, requiring a relatively large outside space.

ANIMAL WELFARE POINT OF VIEW IN CASE OF LAYING HEN POULTRY BIRDS IN BATTERY CAGES

Egg-laying hens housed in battery cages are intensively confined, living in less than half a square foot of space [, and suffer from numerous welfare issues . Cage-free housing for layer hens provides improved welfare, allowing hens space to move more freely and express natural behaviors. Consumers also value animal welfare . However, this does not always manifest in consumer behavior, likely in part because consumers have incomplete information about animal welfare when making purchasing choices . Thus the suffering of farm animals represents losses of both animal welfare and consumer welfare. Starting in 2005, many corporations made commitments to source cage-free eggs, often with deadlines to complete the sourcing several years in the future. As of 2019, nearly 400 retailers, restaurants, and food service companies with operations in the United States (US) have made commitments , and cage-free commitments have also spread globally.

Trends and challenges in cage-free egg production

Cages have been the dominant egg production system for decades. However, concerns about bird welfare are driving many egg producers, retailers and food service companies to ban cage eggs from their supply chains. The European Commission (EC) has also recently committed to prohibiting cage use and should present a legislative proposal to address this issue by 2023.

Responding to the ‘End the Cage Age’ petition, led by 170 NGOs across Europe and signed by 1.4 million citizens, on 10 June 2021 the European Parliament voted on a ban on the use of cages in animal farming. Although the European Union (EU) had already banned the use of conventional cages for layer hens in 2012, the campaigners insisted that this was not enough. Shortly after, on 30 June 2021, the European Commission announced that a legislative proposal will be presented by the end of 2023 to phase out, and finally ban, the use of cages for several farm animals. Far from being spontaneous decisions, these recent announcements come as part of a long sequence of events leading towards cage-free egg production. Even without a legislative ban, numerous large egg producers, retailers, food service companies and hotel chains are already taking action against cage eggs. With this in mind, let’s look at some of the most relevant trends and challenges surrounding cage-free systems.

Evolution of housing systems

Chickens have traditionally been kept in floor systems since their domestication over 8,000 years ago. Backyard chickens, which are still common around the world, are generally housed on the floor and are provided with variable amounts of space. Conventional cages, developed in the 1930s, eventually became the standard housing system as the industrialisation of egg production advanced. These cages brought essential benefits to egg producers, such as more efficient use of the available space, the possibility of a fully automated process, easier management, superior hygiene, lower incidence of infectious diseases, lower feed consumption and lower production costs.

Although successful, cage systems also received early disapproval from some. By the 1960s, animal welfare was gaining in importance in Europe and the use of cages started to be criticised for restricting bird movement and the expression of certain behavioural patterns of laying hens. Furnished cages – also known as enriched, colony or modified cages – were first developed in the 1980s. These represented an attempt to combine the best of two worlds: the advantages of conventional cages in terms of hygiene and production efficiency, together with some of the benefits of cage-free systems. Besides providing more space per hen than their traditional counterpart, furnished cages are typically equipped with a perch, nest, scratching area and nail shortener. The exact provision of each of these elements may vary from one country or region to another.

It is widely recognised that furnished cages increase hens’ behavioural expression compared to conventional cages, besides improving the birds’ physical condition. Nevertheless, the precise degree to which such behaviours can be expressed in furnished cages has also been questioned, since locomotion, ground-scratching, wing-flapping and flying are inherently limited or prevented in all types of caged environments.

Although they allow hens to express their entire behavioural repertoire, cage-free systems present specific challenges for egg producers. Photo: Ronald Hissink

Ongoing pressure on furnished cages

Despite EU-wide legislation that authorises furnished cages, several member states have banned any type of cage for egg production. At the same time, others have also announced plans to ban cages in their territories. Relevant industry stakeholders are also driving egg production into a ‘post-cage era’, not only in the EU but also in the USA and several other countries. In its most recent Egg Track Report, issued in 2020, Compassion in World Farming revealed that dozens of major egg producers, retailers, food service companies and hotel chains, including corporations with a worldwide presence, have committed to banning cage eggs from their supply chains. Some of these companies have already fully transitioned to cage-free eggs, while most others plan to do so by 2025.

Not surprisingly, in those regions the share of eggs produced in cages has sharply decreased in recent years. While in 2008 over two thirds of hens in the EU were housed in cages (68%), by 2020 this figure had dropped to less than half of EU hens (48%). Similarly, while cage-free flocks yielded only 5% of US eggs in 2009, they now account for 29% of all eggs produced and it is estimated that their share will increase to about two thirds of the market by 2026.

Economic impact of welfare requirements

Apart from inspiring amendments to layer hen welfare regulations on other continents, Council Directive 1999/74/EC transformed the landscape of egg production in the EU. In brief, this directive imposed relevant changes on egg producers at two milestones: from 2003, at least 550 cm2 of cage space per hen had to be provided (the former requirement was 450 cm2 per hen), while conventional cages were finally banned in 2012. These changes mean that all layers must now be housed either in non-cage systems (barn/aviary, free-range or organic) or furnished cages (minimum space requirement of 750 cm2 per hen).

Layer hen welfare regulations are costly. The increased space allowance enforced in 2003 raised the cost of egg production by about 3.4%, whereas 2012’s ban on conventional cages (accompanied by the 750 cm2 per hen room expansion) increased the cost by an additional 6.8%. Added to which the cost of egg production in barn/aviary in the EU is 23% greater than it was in pre-2012 cage production (conventional cages, 550 cm2 per hen). These figures are comparable to those of the USA where the cost of producing an egg in furnished cages (753 cm2 per hen) is 13% higher than in conventional cages (516 cm2 per hen), and the cost of egg production in an aviary is 36% more than in conventional cages. For other countries too, there will probably be similar gaps between housing systems in terms of the cost of egg production.

Cage-free challenges

Although they allow hens to express their entire behavioural repertoire, cage-free systems present specific challenges for egg producers. On average, hen mortality rate is greater in cage-free systems, especially in free-range, compared to furnished cages. A greater prevalence of cannibalism, various bacterial infections and internal parasites, plus the occasional occurrence of smothering, explain that difference. Moreover, free-range chickens are at risk of predation and can become infected with diseases, such as avian flu and Newcastle disease, through contact with wild birds. Wet litter and high ammonia content can lead to footpad dermatitis and bumblefoot, a painful footpad infection.

The prevalence of keel bone fractures, a vital welfare concern in layer hens, is higher in non-cage systems compared to cages. Although well-managed cage-free flocks can achieve good performance, their average productivity can be lower in comparison to cage production. Added to which some eggs will be laid on the floor and these have a higher level of bacterial contamination of the eggshell. Another negative consequence of floor eggs is the possible triggering of broodiness which interrupts egg production in the affected hens. Non-cage systems also provide hens with more space, thereby increasing bird movement and energy expenditure. Therefore, feed intake and the feed conversion ratio (FCR) are typically higher in non-cage systems compared to cages. All in all, there are many challenges to be overcome when switching to cage-free production.

Consumer-led revolution

Cage-free is expected to continue and develop and take full control over the markets of most developed countries within the next five to ten years.This is a consumer-led revolution. Supermarkets and fast-food chains, which are always the most sensitive to consumer wishes, identified the shift and acted accordingly.So, for example, McDonalds and Woolworth, a large Australian supermarket chain, set a timetable for becoming 100% cage-free, informing their suppliers that they had to become cage-free within a certain time at the same price level.As with many other changes, the shift wasn’t led by government regulation. In fact, the European establishment resisted it, trying to protect the enriched cage regulations that they were heavily invested in.As with many other changes, the shift wasn’t led by government regulation. In fact, the European establishment resisted it, trying to protect the enriched cage regulations that they were heavily invested in.There is a necessity for regulation or standards so that the consumer will not be deceived. In some areas, these regulations will be official and in others they can be formulated and policed by animal welfare organisations, such as the Australian RSPCA animal welfare organisation, which prepared a standard and polices it.

The full implications of the cage-free revolution are not clear yet, but the impact is already evident almost everywhere, forcing consumers, producers, suppliers, retailers and regulators to adjust to a changing reality.

LATEST NOTIFICATION OF INDIAN GOVERNMENT RELATED TO BATTERY CAGES:

Prevention of Cruelty to animals (Egg Laying Hens in Battery Cages ) Rules s – 2023

Compiled & Shared by- Team, LITD (Livestock Institute of Training & Development)

Image-Courtesy-Google

Reference-On Request.