An Insight on the Control and Managemental Strategies of Major Parasitic Infections of Goats

Dr. Paramjit Kaur

Associate Professor, Department of Veterinary Parasitology

Guru Angad Dev Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, Ludhiana

Goat industry is mounting over the years as10.1% increase in the goat population is recorded with total 148.88 million goats in India as per 20th livestock census. Small ruminants hold an important niche for sustainable agriculture in developing countries and support a variety of socio-economic functions worldwide. The productivity of the goat industry is influenced by a variety of constraints allied with management and disease. The respiratory infections, skin diseases and gastrointestinal (GIT) diseases including diarrhoea are ranked as important health problems in goats throughout the world (Castro-Hermida et al., 2007). Thus, GIT parasites pose a serious threat to small ruminant production systems as it accounted for about 82.7% of the total losses in goats in India (Pawaiya et al., 2017). Parasites are broadly classified into endoparasites (helminthes, protozoa) and ectoparasites (ticks, mites, lice, fleas). Goat being the poor man‟s cow contributes significantly in economy of the landless marginally farmers as they rear them for their livelihood and is also a good source of food, fibre, skin and manure. In Indian scenario majority of the goat farmers raised their animals on the extensive grazing management that makes them more susceptible to GIT parasitic infections. These parasites are the major constraints in small and large goat production of the tropical and subtropical parts of the world due to morbidities, reduce weight gain and other production losses as the subclinical infections more common that are difficult to diagnose. The impact of parasites can vary in general due to ecological factors suitable for diversified hosts and parasite species; the epidemiology of GIT parasites in livestock varied depending on the local climatic condition, such as humidity, temperature, rainfall, and vegetation and management practices. These factors largely determine the incidence and severity of various parasitic diseases in a region. An overall prevalence of GIT parasite in sheep and goat of different agroclimatic zones of Punjab 83-84% was reported (Singh et al., 2017; Pawar et al., 2019).

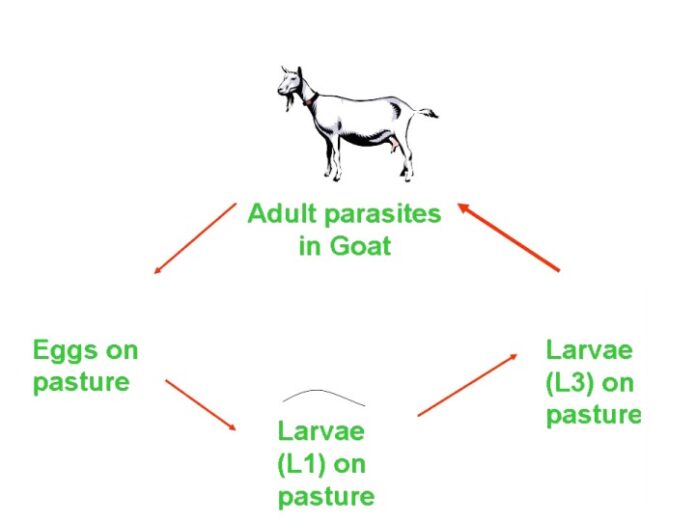

Gastrointestinal nematodes (GIN) parasites: Haemonchus contortus, Trichostrongylus circumcincta, Ostertagia trifurcata, Trichostrongylus axei, Strongyloides species, Cooperia, Paracooperia. Among these nematodes, H. contortus is the most pathogenic predominant, haematophagous parasite (0.05 ml/ parasite/day) and estimated cost incurred on its treatment alone in India is $103 million per annum (Peter & Chandrawathani, 2005). The life cycle of GIN parasites is direct with free living developmental stages (eggs, larval stages L1-L3), parasitic forms (larval stage L3 to L5 and adults). The migration of the larvae in the host cause substantial damage to abomasum (Haemonchus, Ostertagia and T. axei) and Intestine (Cooperia, Paracooperia, Trichuris spp.) Oestertagiosis and trichostrongylosis have similar type of pathogenesis that cause inflammation and leakage of protein into the intestinal tract resulting protein losing gastro-enteropathy. Clinical signs of GIN parasites are anemia, bottle jaw, and weakness, reluctance to move, exercise intolerance, and weight loss. The change in the colour of the faeces is one of the indicators in acute infections; tarry colour faeces in acute haemonchosis, black colour in trichostrongylosis, and bright greenish colour in oestertagiosis and mucoid greenish diarrhoea in oesophagostomosis (pimply gut infection). Young animals are most susceptible than adults. Severe blood and protein loss into the abomasum and intestine due to damage caused by the parasites often results in oedema, hypoproteinemia and bottle jaw condition. In field conditions mostly mixed infections of above GIN parasites are predominant, so it becomes difficult to rule out these infections routinely in morbid cases. However, if mortality occurs then postmortem examination confirms the genus specific parasites.

Treatment strategies for GIN parasites: GIN parasites are treated and control by broad spectrum anthelmintics: benzimidazole, tetrahydropyrimidines, cholinergic agonists and macrocyclic lactones. The frequent use of anthelmintic and lack of awareness among the farmers about the resistance in parasites to particular drug, anthelmintic resistance (AR) has become a major constraint in the control of the GIN parasites. AR development is a highly multifaceted process which is affected via the host, the parasite, type of anthelmintic and its utilization, animal management and climatic characteristics. Thus, enhancing the challenges for developing the controlling and preventing measures that could vary based on the animal production systems. Only 20% animals in herds are the shedder for 80% of the parasite, accordingly treatment should be given to the targeted animals only. The target selective treatment (TST) based on five check points; eye evaluation for anaemia, back for body condition scoring, tail for soiling with faeces, jaw for swelling and rough hair coat and use of FAMACHA tool. The dose, route and body weight should take into consideration before administration to overcome the problem of anthelmintic resistance. Fasting of animals for up to 24 hours may improve efficacy of dewormers, especially when using benzimidazoles and ivermectin.

The alternative approaches to slow down the development of AR are the development of resistant breeds by cross breeding programme, use of bio-control agents like plants (leguminous grasses), or bacteria (Bacillus thuringiensis), predacious fungi (Duddingtonia flagrans, Arthobotrys spp. & Monacrosporium spp), endoparasitic fungi (Drechmeria coniospora and Harposporium anguillulae) that kill the parasitic and free-living stages of the nematode parasites. Predacious fungi produce specialized adhesive knobs, networks, rings on the mycelium that traps the nematode, while endoparasitic fungi‟s spores penetrate the cuticle of the parasites and lead to death of worm lodged in the gut. Forage plants that contain high levels of condensed tannins include Sericea lespedeza (warmseason legume), birds foot trefoil (perennial legume) and chicory (leafy perennial). Condensed tannins have been shown to reduce gastrointestinal parasite loads in goats by reducing worm fertility, eliminating adult worms, and retarding the establishment of incoming larvae (Waller, 2006).

General control strategies: Proper cleanliness in and around the shed area, proper stocking density to avoid overcrowding, immediate removal of dung pat and disposal in a pit to heap so that eggs, larvae, cyst, or other stages of parasites are killed due to heat generated during composting (Williams and Warren, 2004). Provide balance diet with vitamin and minerals as it aid in development of resistance to parasites, and results into functional immunity against the parasites (Hughes and Kelly, 2006).

Pasture management: It includes pasture rest, rotation and burning and ploughing of the pasture. The already grazed pasture by sheep and goats should be given rest for at least two months in tropical areas, upto 6 months in temperate areas in order to destroy the free living developmental stages and for the dilution of the contaminated pastures.

Grazing strategies: The grazing management includes animal density (5–7 goats/acre) in order to avoid the overstocking, zero grazing or clean or safe pastures especially for the young animals, alternative species wise grazing and age wise grazing. Under Indian condition the grazing time is more important criteria than pasture management due to non-availability of private land or large paddocks for grazing. It is advised to take the animals for grazing when there is sufficient sunlight, not too early in morning or in late evening or in the rainy day, as most of the infective larval stages available on the tip of the forages. Most of the endoparasitic infections predominate in rainy season so keep the animals on intensive system during this season. Graze the animals on the grass having height up to 10 cm from the ground, as the larvae or intermediate host prefers to be in the soil, on the dry grass.

Trematodes/Flukes: These are the snail borne parasites. The commonly flukes in the goats are different types of the paramphistomes (ruminal flukes) and Fasciola (liver fluke). Fasciola hepatica and F. gigantica (common liver fluke) requires Lymnaea luteola and L. auricularia snail. Dicrocoelium dendriticum is comparatively small liver fluke life cycle includes snails and ants as intermediate host. These burrow tunnels in the liver, causing scarring as the body tries to repair the damage. Because scar tissue is not functional, the liver loses part of its normal function, which includes filtering the blood of toxins and waste products. The accumulation of these toxins in the animal‟s blood can severely damage other organs, including the brain. Clinical signs of trematodal infection are poor appetite, lethargy, weight loss, jaundice, bottle jaw condition, acute cases die suddenly, profuse watery diarrhoea in amphitomosis. Antitrematodal drugs are rafoxanide (7.5 mg/kg orally), oxyclozanide (15 mg/kg orally) and nitroxynil (10 mg/kg, s/c).

Cestodes/Tapeworm: These are ribbon or tape like worms found in the GIT tract includes Moniezia spp., Aviteillina and Stilesia spp. do not show any clinical signs except in case of heavy infections cause intestinal obstruction that predisposing the animals to enterotoxemia and, potentially, intestinal rupture. Tapeworms have indirect life that includes oribatid mites as intermediate host. Presence of yellow or white segments of cooked rice grain is indicative of the tapeworm infections. The drug of choice for tapeworm is praziquantel @ 10 mg/kg, but fenbendazole (10 mg/kg), albendazole (10mg/kg), oxfenbendazole (10 mg/kg) and niclosamide (50 mg/kg) orally also found effective.

Protozoan Parasites: Major protozoan infections of goats are coccidiosis, cryptosporidiosis and toxoplasmosis. Coccidiosis is a predominant enteric parasitic infection, 13 species of Eimeria worldwide, but from the Punjab state seven species of Eimeria; E. ninakohlyakimovae, E. arloingi,E. caprovina, E.alijevi, E. christenseni, E. hirci and E. jolichevi are reported (Kaur et al., 2019). Kids between 3- 4 months are the most susceptible due to no immunity to these parasites. Adult goats normally shed low numbers of oocysts and a source of infections to the young animals. Coccidiosis is clinically characterized based on bloody diarrhea not as common as in calves, straining, weight loss and dehydration and death. Subclinical infection can result in poor weight gain, poor hair coat, and an unthrifty appearance. The anticoccidials approved for use in goats are decoquinate (0.5- 1 mg/kg b.wt), monensin (20 g/ton of feed) and amprolium, @ 25-50 mg/kg/day for prevention (for 21 days) and for treatment (5 days). Two form of cryptosporidiosis in goats are as clinical neonatal diarrhoeic syndrome and asymptomatic form (Castro-Hermida et al. 2007). Clinical entity includes depression, anorexia, abdominal pain accompanied by abdominal discomfort and white to yellowish diarrhea with unpleasant odour.

Toxoplasmosis is abortion causing disease caused by apicomplexan unicellular parasite Toxoplasma gondii. Goats get infected with T. gondii when they ingest the oocyst while grazing or feed on roughages contaminated with cat feces. In most cases, the adult ewe or doe does not show any signs of infection before or after the abortion. If clinical signs are noticed, they usually include fever and neurological problems. Ewes that are infected before breeding usually will not abort. Those that are infected early in their pregnancy (30-60 days) will often resorb or mummify the fetus. In abortion cases examination of the placenta for demonstration of the organisms, necropsy revealed small areas of necrosis and calcification that appear grayish to yellow on cotyledons. It is also possible to test the placenta, and fetal fluids, brain, muscles, or lungs for the presence of the T. gondii organism. The presence of antibodies in 39.60% tested goats from the Punjab by ELISA test observed. The animals with history of abortion and farms having access to the cats were the main risk factor responsible of toxoplasmosis (Pandit et al., 2021). The control programme should focus on the prevention of feed water contamination with the cat faeces and proper carcass disposal of dead animals, aborted foetus and placenta in order to avoid access to the cats.

Haemoparasitic infections: The tick borne haemoprotozoan infectio of goat are anaplsmosis, babesios and theileriosis. Anaplasmosis caused by Anaplasma ovis , transmitted by ticks of genera Boophilus, Rhipicephalus, Ixodes and Hyalomma. Mechanical transmission may occur via biting dipterans flies, mosquitoes and by iatrogenic route of use of contaminated needles or dehorning or other surgical instruments. Babesiosis caused by Babesia ovis and Babesia motasi, transmitted by Rhipicephalus bursa and Haemaphysalis spp., respectively. However, malignant theileriosis is caused by Theileria ovis, T. separata, and T. recondite and T. hirci which are transmitted by Hyalomma anatolicum anatolicum. The clinical symptoms of all these haemoparasitic infection generally overlapping are fever, anemia, jaundice, loss of coordination, breathlessness, diarrhoea, prostration and death. The microscopic examination of blood smears stained with Romanowsky stain prior the treatment is mandatory, to decide the precise treatment of the exact cause of infection. The treatment regimen for anaplasmosis includes long-acting oxytetracycline at a dosage of 20 mg/kg, IM. Babesiosis can be treated with diminazene @ 3.5 mg/kg, IM and imidocarb @ 1.2 mg/kg subcuteneously. Buparvaquone is effective against theileriosis at a dose rate of 20 mg/kg body weight, intramuscularly.

Ectoparasites: Goats can suffer from a range of external parasites; ticks, mites, lice, fleas and flies. Ticks are the major ectoparasites of the livestock and in India Boophilus microplus, Hyalomma anatolicum anatolicum, Haemaphysalis spp affects the goats. Ticks cause direct (tick worry, tick toxicosis) and indirect (reduced growth, milk and meat production, damaged hides and skins, myiasis, vector borne transmission potential) losses to the animals. Acaricide application is the most widely used and effective method of tick control but it led to development of acaricide resistance. Ticks can live on the ground for up to 300 days without feeding. Treat the animals with acaricides in case of heavy tick infestation. Otherwise, remove the tick manually when present in little number. Quarantine measures of the new entry into the herd and treatment with acaricides should be followed. Lice (permanent ectoparasite) unlike ticks have a marked degree of host specificity, even sheep and goats having their own distinct species. Linognatus, Damalinia species are found in goats. Lousiness causes unthriftiness, matted, dull fleece with tufts of wool, reduced weight gain and production loss. Lice are also associated with development of cockle. Spraying or dipping with insecticides is effective, but it should always be carried out twice, the first time to kill the lice currently on the body, the second 14 days later to kill lice hatching from eggs present at first treatment.

A mite of genera Psoroptes, Sarcoptes and Demodex causes the mange in the goats. Sarcoptes scabei var capri is more pathogenic mite burrows deep into the skin, cause small red papules of the skin, severe itching and scratching, loss of hair, thick brown scabs and thickening and wrinkling of surrounding skin. Demodecosis or follicular or red mange caused by Demodex that invades hair follicles and sebaceous glands of all species of domestic animals, more severe in goats. It forms thick scabs overlaying the skin round the eyelids, nose, the brisket, lower neck, forearm and shoulder and the tips of the ear. Demodectic mange causes small nodules and pustules which may develop into large abscess. In severe cases there may be a general hair loss and thickening of the skin. Psoroptes is a non-borrowing mite live on the surface of the skin and most rarely found in goats than sheep (sheep scab).

Different categories of insecticide and acaricides are commercially available are Synthetic pyrethroids : deltamethrin (12.5%; 2-3 ml/L ticks, 4-6 ml/ L for mites and 1-1.5 ml/L for lice), cypermethrin (10%;1 ml/L on body, 5 ml/L), flumethrin (6% solution, 10% pour on; 1ml/2 liter in water, 1ml/10 kg b. wt as pour on preparation); Avermectins: doramectin and ivermectin (0.2 mg/kg b.wt s/c or 2.5 ml/10 kg b.wt orally); Formamidines: amitraz (12.5%; 2 ml/L of water for ticks, 4 ml/L for mite, lice). Precautionary measure for these drugs should be taken care off are use only when required as injudicious use lead to resistance, read the instruction given on label carefully, DO NOT treat goats just before slaughter, check the withdrawal time of acaricides. Seal with cement or mud all cracks in the floor and walls of shed housing.

References

Castro-Hermida, J.A., Almeida, A., González-Warleta, M., Correira, D.A. J., Rumbou. L. C. & Mezo, M. (2007). Occurrence of Cryptosporidium parvum in healthy adult domestic ruminants. Parasitology Research, 101, 1443-1448.

Hughes, S. & Kelly, P. (2006). Interactions of malnutrition and immune impairment, with specific reference to immunity against parasites. Parasite Immunology, 28, 577-588.

Kaur, S., Singla, L. D., Sandhu, B.S., Bal, M.S, & Kaur, P. (2018). Coccidiosis in goats: Pathological observations on intestinal developmental stages and anticoccidial efficacy of amprolium. Indian Journal of Animal Research, 65, 245-249

Pandit, D., Bal, M.S., Kaur, P., Singla, L.D., Mahajan, V., & Setia, R.K. (2021). Seroprevalence and spatial distribution of toxoplasmosis in relation to various risk factors in small ruminants of Punjab, India. Indian Journal of Animal Research DOI: 10.18805/IJAR.B- 4358

Pawaiya, R. V. S., Singh, D. D., Gangwar, N. K., Gururaj, K., Kumar, V., Paul, S., & Singh, S.

- (2017). Retrospective study on mortality of goats due to alimentary system diseases in an organized farm. Small Ruminant Research, 149, 141-146.

Pawar, P. D., Singla, L. D., Kaur, P., Bal. M. S., & Javed, M. (2019). Evaluation of multiple anthelmintic resistance for gastrointestinal nematodes using different faecal egg count reduction methods in small ruminants of Punjab, India. Acta Parasitologica, 64(3), 456- 463

Peter, J. W., & Chandrawathani, P. (2005). Haemonchus contortus: parasite problem No. 1 from Tropics – Polar Circle. Problems and prospects for control based on epidemiology. Tropical Biomedicine, 22(2), 131–137.

Singh, E., Kaur, P., Singla, L. D., & Bal, M. S. (2017). Prevalence of gastrointestinal parasitism in small ruminants in western zone of Punjab, India. Veterinary World, 10(1), 61-66.

Waller, P. J. (2006). Sustainable nematode parasite control strategies for ruminant livestock by grazing management and biological control. Animal Feed Science and Technology 126, 277- 289.

Williams, B. & Warren, J. (2004). Effects of spatial distribution on the decomposition of sheep faeces in different vegetation types. Agriculture Ecosystem Environment 103, 237–243.

Control & Management of Major Parasitic Diseases of Livestock in India