COMPILED & EDITED BY-DR K.OJHA, ANIMAL BEHAVIORIST

ANIMAL COMMUNICATION: AN ALTERNATIVE THERAPY TO HEAL PEOPLE & ANIMAL

Animal communication

-

Communication is when one animal transmits information to another animal causing some kind of change in the animal that gets the information.

-

Communication is usually between animals of a single species, but it can also happen between two animals of different species.

-

Animals communicate using signals, which can include visual; auditory, or sound-based; chemical, involving pheromones; or tactile, touch-based, cues.

-

Communication behaviors can help animals find mates, establish dominance, defend territory, coordinate group behavior, and care for young.

Animals communicate in a silent language, and humans communicate in a verbal language. This silent language is called telepathy which means feeling across a distance. Communicating telepathically with animals means we are mentally sending and receiving messages. It involves the direct transmission of feelings, emotions, intentions, thoughts, mental images, impressions, sensations, and pure knowing. In this kind of communication you do not read body language or make guesses based on behaviour. Telepathic communication after all, is an innate ability of all beings.

So even though we were all born with the ability, and it was very natural as young children and babies, it has been forgotten to most of us as we grew up. Telepathy can be relearnt and used once again to communicate with the natural world, and form wonderful bonds and understanding with our animal friends. Animals are already masters of telepathic communication and talk to each other in this way and to humans, if they allow themselves to tune in or are perceptive to them. It is just like learning a different language.

When we meet someone who does not speak our language, we don’t assume that they have nothing to say, we just can’t understand them. If we wish to communicate with them we either need to learn their language or use an interpreter, such as an animal communicator.

If you have a close relationship with your animal companion, you can be sure you are already communicating with them. You just may not realize that you are communicating with your animals because you think that the thoughts and feelings are your own.

Telepathic communication functions successfully both in person and at a distance. By distance I mean you can be on the other side of the world and still successfully make a connection with your animal or any animal. It functions similarly as do call letters of a radio station tuning in a radio station.

We can learn so much from animals, such as how to live in balance and harmony with ourselves, and with others on the earth. Also how to accept and love ourselves unconditionally the way our animals companions do. Telepathic communication boosts the understanding, joy and richness possible in relationships between humans and their companion animals and in fact all species.

The word ‘Telepathy’ is derived from the Greek word ‘Tele’ meaning distance and ‘path’ meaning feeling. Thus telepathic communication means communication through the transfer of thoughts. It is a two-way conversation using all five senses.

In fact, it is not limited to animals alone, we can also communicate telepathically with birds, insects, fish, plants and even landscapes. All of nature with all its species, including us, are highly sentient and intelligent and gifted with the language of telepathy.

In our day to day lives, most of us tend to forget this innate ability of ours. But all we need to do is rediscover it. With patience and practice, it is possible for anybody to connect telepathically with animals and nature.

Animal Communicators, also known as Pet Psychics, Pet Mediums, and Animal Telepaths, can telepathically and intuitively connect with dogs, cats, horses, and other animals to uncover sources of discomfort, dis-ease, bad habits, and behaviors. Animal telepathy also discovers how an animal feels about the world around them, their likes, dislikes, wants, needs, desires, sense of humor, wisdom, and purpose in our lives.

Have you ever wondered how ants follow what seem to be invisible trails leading to food?

Why male dogs mark their territory by peeing on bushes and lampposts when you take them for a walk?

What birds are saying to one another when they chirp outside your window?

The ability to communicate effectively with other individuals plays a critical role in the lives of all animals. Whether we are examining how moths attract a mate, ground squirrels convey information about nearby predators, or chimpanzees maintain positions in a dominance hierarchy, communication systems are involved. Here, I provide a primer about the types of communication signals used by animals and the variety of functions they serve.

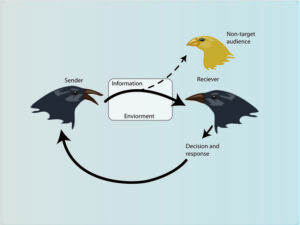

Animal communication is classically defined as occurring when “…the action of or cue given by one organism [the sender] is perceived by and thus alters the probability pattern of behavior in another organism [the receiver] in a fashion adaptive to either one both of the participants” (Wilson 1975). While both a sender and receiver must be involved for communication to occur (Figure 1), in some cases only one player benefits from the interaction. For example, female Photuris fireflies manipulate smaller, male Photinus fireflies by mimicking the flash signals produced by Photinus females. When males investigate the signal, they are voraciously consumed by the larger firefly (Lloyd 1975; Figure 2). This is clearly a case where the sender benefits and the receiver does not. Alternatively, in the case of fringe-lipped bats, Trachops cirrhosus, and tungara frogs, Physalaemus pustulosus, the receiver is the only player that benefits from the interaction. Male tungara frogs produce advertisement calls to attract females to their location; while the signal is designed to be received by females, eavesdropping fringe-lipped bats also detect the calls, and use that information to locate and capture frogs (Ryan et al. 1982). Despite these examples, there are many cases in which both the sender and receiver benefit from exchanging information. Greater sage grouse nicely illustrate such “true communication”; during the mating season, males produce strutting displays that are energetically expensive, and females use this honest information about male quality to choose which individuals to mate with (Vehrencamp et al. 1989).

Figure 1

A model of animal communication.

Figure 2:

Photinus fireflies.

Courtesy of Tom Eisner.

Signal Modalities

Animals use a variety of sensory channels, or signal modalities, for communication. Visual signals are very effective for animals that are active during the day. Some visual signals are permanent advertisements; for example, the bright red epaulets of male red-winged blackbirds, Agelaius phoeniceus, which are always displayed, are important for territory defense. When researchers experimentally blackened epaulets, males were subject to much higher rates of intrusion by other males (Smith 1972). Alternatively, some visual signals are actively produced by an individual only under appropriate conditions. Male green anoles, Anolis carolinensis, bob their head and extend a brightly colored throat fan (dewlap) when signaling territory ownership.

Acoustic communication is also exceedingly abundant in nature, likely because sound can be adapted to a wide variety of environmental conditions and behavioral situations. Sounds can vary substantially in amplitude, duration, and frequency structure, all of which impact how far the sound will travel in the environment and how easily the receiver can localize the position of the sender. For example, many passerine birds emit pure-tone alarm calls that make localization difficult, while the same species produce more complex, broadband mate attraction songs that allow conspecifics to easily find the sender (Marler 1955). A particularly specialized form of acoustic communication is seen in microchiropteran bats and cetaceans that use high-frequency sounds to detect and localize prey. After sound emission, the returning echo is detected and processed, ultimately allowing the animal to build a picture of their surrounding environment and make very accurate assessments of prey location.

Compared to visual and acoustic modalities, chemical signals travel much more slowly through the environment since they must diffuse from the point source of production. Yet, these signals can be transmitted over long distances and fade slowly once produced. In many moth species, females produce chemical cues and males follow the trail to the female’s location. Researchers attempted to tease apart the role of visual and chemical signaling in silkmoths, Bombyx mori, by giving males the choice between a female in a transparent airtight box and a piece of filter paper soaked in chemicals produced by a sexually receptive female. Invariably, males were drawn to the source of the chemical signal and did not respond to the sight of the isolated female (Schneider 1974; Figure 3). Chemical communication also plays a critical role in the lives of other animals, some of which have a specialized vomeronasal organ that is used exclusively to detect chemical cues. For example, male Asian elephants, Elaphus maximus, use the vomeronasal organ to process chemical cues in female’s urine and detect if she is sexually receptive (Rasmussen et al. 1982).

Figure 3

Male silkmoths are more strongly attracted to the pheromones produced by females (chemical signal) than the sight of a female in an airtight box (visual signal).

Tactile signals, in which physical contact occurs between the sender and the receiver, can only be transmitted over very short distances. Tactile communication is often very important in building and maintaining relationship among social animals. For example, chimpanzees that regularly groom other individuals are rewarded with greater levels of cooperation and food sharing (de Waal 1989).

For aquatic animals living in murky waters, electrical signaling is an ideal mode of communication. Several species of mormyrid fish produce species-specific electrical pulses, which are primarily used for locating prey via electrolocation, but also allow individuals searching for mates to distinguish conspecifics from heterospecifics. Foraging sharks have the ability to detect electrical signals using specialized electroreceptor cells in the head region, which are used for eavesdropping on the weak bioelectric fields of prey (von der Emde 1998).

Signal Functions

Some of the most extravagant communication signals play important roles in sexual advertisement and mate attraction. Successful reproduction requires identifying a mate of the appropriate species and sex, as well as assessing indicators of mate quality. Male satin bowerbirds, Ptilonorhynchus violaceus, use visual signals to attract females by building elaborate bowers decorated with brightly colored objects. When a female approaches the bower, the male produces an elaborate dance, which may or may not end with the female allowing the male to copulate with her (Borgia 1985). Males that do not produce such visual signals have little chance of securing a mate. While females are generally the choosy sex due to greater reproductive investment, there are species in which sexual roles are reversed and females produce signals to attract males. For example, in the deep-snouted pipefish, Syngnathus typhle, females that produce a temporary striped pattern during the mating period are more attractive to males than unornamented females (Berglund et al. 1997).

Communication signals also play an important role in conflict resolution, including territory defense. When males are competing for access to females, the costs of engaging in physical combat can be very high; hence natural selection has favored the evolution of communication systems that allow males to honestly assess the fighting ability of their opponents without engaging in combat. Red deer, Cervus elaphus, exhibit such a complex signaling system. During the mating season, males strongly defend a group of females, yet fighting among males is relatively uncommon. Instead, males exchange signals indicative of fighting ability, including roaring and parallel walks. An altercation between two males most often escalates to a physical fight when individuals are closely matched in size, and the exchange of visual and acoustic signals is insufficient for determining which animal is most likely to win a fight (Clutton-Brock et al. 1979).

Communication signals are often critical for allowing animals to relocate and accurately identify their own young. In species that produce altricial young, adults regularly leave their offspring at refugia, such as a nest, to forage and gather resources. Upon returning, adults must identify their own offspring, which can be especially difficult in highly colonial species. Brazilian free-tailed bats, Tadarida brasiliensis, form cave colonies containing millions of bats; when females leave the cave each night to forage, they place their pup in a crèche that contains thousands of other young. When females return to the roost, they face the challenge of locating their own pups among thousands of others. Researchers originally thought that such a discriminatory task was impossible, and that females simply fed any pups that approached them, yet further work revealed that females find and nurse their own pup 83% of the time (McCracken 1984, Balcombe 1990). Females are able to make such fantastic discriminations using a combination of spatial memory, acoustic signaling, and chemical signaling. Specifically, pups produce individually-distinct “isolation calls”, which the mother can recognize and detect from a moderate distance. Upon closer inspection of a pup, females use scent to further confirm the pup’s identity.

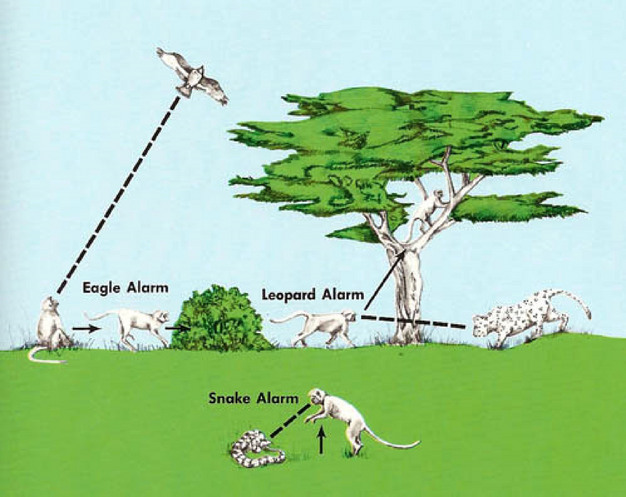

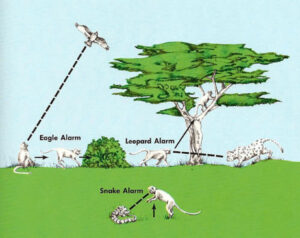

Many animals rely heavily on communication systems to convey information about the environment to conspecifics, especially close relatives. A fantastic illustration comes from vervet monkeys, Chlorocebus pygerythrus, in which adults give alarm calls to warn colony members about the presence of a specific type of predator. This is especially valuable as it conveys the information needed to take appropriate actions given the characteristics of the predator (Figure 4). For example, emitting a “cough” call indicates the presence of an aerial predator, such as an eagle; colony members respond by seeking cover amongst vegetation on the ground (Seyfarth & Cheney 1980). Such an evasive reaction would not be appropriate if a terrestrial predator, such as a leopard, were approaching.

Figure 4

Vervet monkeys.

Many animals have sophisticated communication signals for facilitating integration of individuals into a group and maintaining group cohesion. In group-living species that form dominance hierarchies, communication is critical for maintaining ameliorative relationships between dominants and subordinates. In chimpanzees, lower-ranking individuals produce submissive displays toward higher-ranking individuals, such as crouching and emitting “pant-grunt” vocalizations. In turn, dominants produce reconciliatory signals that are indicative of low aggression. Communication systems also are important for coordinating group movements. Contact calls, which inform individuals about the location of groupmates that are not in visual range, are used by a wide variety of birds and mammals.

Overall, studying communication not only gives us insight into the inner worlds of animals, but also allows us to better answer important evolutionary questions. As an example, when two isolated populations exhibit divergence over time in the structure of signals use to attract mates, reproductive isolation can occur. This means that even if the populations converge again in the future, the distinct differences in critical communication signals may cause individuals to only select mates from their own population. For example, three species of lacewings that are closely related and look identical are actually reproductively isolated due to differences in the low-frequency songs produced by males; females respond much more readily to songs from their own species compared to songs from other species (Martinez, Wells & Henry 1992). A thorough understanding of animal communication systems can also be critical for making effective decisions about conservation of threatened and endangered species. As an example, recent research has focused on understanding how human-generated noise (from cars, trains, etc) can impact communication in a variety of animals (Rabin et al. 2003). As the field of animal communication continues to expand, we will learn more about information exchange in a wide variety of species and better understand the fantastic variety of signals we see animals produce in nature.

Glossary

Vomeronasal organ – auxiliary olfactory organ that detects chemosensory cues

Altricial – the state of being born in an immature state and relying exclusively on parental care for survival during early development

Refugia – areas that provide concealment from predators and/or protection from harsh environmental conditions

Conspecifics – organisms of the same species

Communication takes many forms

Communication—when we’re talking about animal behavior—can be any process where information is passed from one animal to another causing a change or response in the receiving animal.

Communication most often happens between members of a species, though it can also take place between different species. For instance, your dog may bark at you to ask for a treat! Some species are very social, living in groups and interacting all the time; communication is essential for keeping these groups cohesive and organized. However, even animals that are relative loners usually have to communicate at least a little, if only to find a mate.

What forms can communication behaviors take? Well, animal sensory systems vary quite a great deal. For instance, a dog’s sense of smell is 40 times more acute than ours!^22squared Because of this sensory diversity, different animals communicate using a wide range of stimuli, known collectively as signals.

Below are some common types of signals:

- Pheromones—chemicals

- Auditory cues—sounds

- Visual cues

- Tactile cues—touch

In some cases, signals can even be electric!

Where does this diversity of communication behaviors come from? Like other traits, communication behaviors—and/or the capacity for learning these behaviors—arise through natural selection. Heritable communication behaviors that increase an organism’s likelihood of surviving and reproducing will tend to persist and become common in a population or species.

In the rest of the article, we’ll look at some examples of the many ways that animals can communicate with one another.

Pheromones

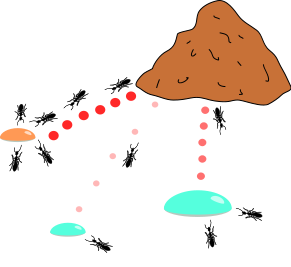

A pheromone is a secreted chemical signal used to trigger a response in another individual of the same species. Pheromones are especially common among social insects, such as ants and bees. Pheromones may attract the opposite sex, raise an alarm, mark a food trail, or trigger other, more complex behaviors.

The diagram below shows pheromone trails laid down by ants to direct others in the colony to sources of food. When a food source is rich, ants will deposit pheromone on both the outgoing and return legs of their trip, building up the trail and attracting more ants. When the food source is about to run out, the ants will stop adding pheromone on the way back, letting the trail fade out^{3,4}3,4start superscript, 3, comma, 4, end superscript.

Image credit: Knapsack ants by Dake, CC BY 2.5

Ants also use pheromones to communicate their social status, or role, in the colony, and ants of different “castes” may respond differently to the same pheromone signals^33cubed. A squashed ant will also release a burst of pheromones that warns nearby ants of danger—and may incite them to swarm and sting^{5,6}5,6start superscript, 5, comma, 6, end superscript.

Dogs also communicate using pheromones. They sniff each other to collect this chemical information, and many of the chemicals are also released in their urine. By peeing on a bush or post, a dog leaves a mark of its identity that can be read by other passing dogs and may stake its claim to nearby territory^{7,8}7,8start superscript, 7, comma, 8, end superscript.

Auditory signals

Auditory communication—communication based on sound—is widely used in the animal kingdom.

Auditory communication is particularly important in birds, who use sounds to convey warnings, attract mates, defend territories, and coordinate group behaviors. Some birds also produce birdsong, vocalizations that are relatively long and melodic and tend to be similar among the members of a species.

Image credit: Barn swallow (Hirundo rustica rustica) singing by Charles J. Sharp, CC BY-SA 4.0

Many non-bird species also communicate using sound:

- Monkeys cry out a warning when a predator is near, giving the other members of the troop a chance to escape. Vervet monkeys even have different calls to indicate different predators.

- Bullfrogs croak to attract female frogs as mates. In some frog species, the sounds can be heard up to a mile away!

- Gibbons use calls to mark their territory, keeping potential competitors away. A paired male and female, and even their offspring, may make the calls together.

Water, like air, can carry sound waves, and marine animals also use sound to communicate. Dolphins, for instance, produce various noises—including whistles, chirps, and clicks—and arrange them in complex patterns. The idea that this might represent a form of language is intriguing but controversial^99start superscript, 9, end superscript.

Visual signals

Visual communication involves signals that can be seen. Examples of these signals include gestures, facial expressions, body postures, and coloration.

Gesture and posture are widely used visual signals. For instance, chimpanzees communicate a threat by raising their arms, slapping the ground, or staring directly at another chimpanzee. Gestures and postures are commonly used in mating rituals and may place other signals—such as bright coloring—on display.

Facial expressions are also used to convey information in some species. For instance, what is known as the fear grin—shown on the face of the young chimpanzee below—signals submission. This expression is used by young chimpanzees when approaching a dominant male in their troop to indicate they accept the male’s dominance.

Image credit: The ‘fear grin’ by CK-12 Foundation, CC BY-NC 3.0

Changes in coloration also serve as visual signals. For instance, in some species of monkeys, the skin around a female’s reproductive organs becomes brightly colored when the female is in the fertile stage of her reproductive cycle. The color change signals that the female can be approached by suitors.

An organism’s general coloration—rather than a change in color—may also act as a visual signal^11start superscript, 1, end superscript. For instance, the bright coloration of some toxic species, such as the poison dart frog, acts as a do-not-eat warning signal to predators.

Image credit: Ranitomeya amazonica by Vir Vikram Singh, CC BY-SA 3.0

Tactile signals—touch

Tactile signals are more limited in range than the other types of signals, as two organisms must be right next to each other in order to touch start superscript, , end superscript. Still, these signals are an important part of the communication repertoire of many species.

Tactile signals are fairly common in insects. For instance, a honeybee forager that’s found a food source will perform an intricate series of motions called a waggle dance to indicate the location of the food. Since this dance is done in darkness inside the nest, the other bees interpret it largely through touch start superscript, 11, comma, 12, end superscript.

Tactile signals also play an important role in social relationships. For instance, in many primate species, members of a group will groom one another—removing parasites and performing other hygiene tasks start superscript, 13, end superscript. This largely tactile behavior reinforces cooperation and social bonds among group members start superscript, 14, end superscript.

Image credit: Macaca fuscata, social grooming by Noneotuho, CC BY-SA 3.0

Tactile stimuli also play a role in the survival of very young organisms. For instance, newborn puppies will instinctively knead at their mother’s mammary glands, causing the release of the hormone oxytocin and production of milk start superscript, 15, end superscript.

What is communication used for?

As the examples above illustrate, animals communicate using many different types of signals, and they also use these signals in a wide range of contexts. Here are some of the most common functions of communication:

- Obtaining mates.Many animals have elaborate communication behaviors surrounding mating, which may involve attracting a mate or competing with other potential suitors for access to mates.

- Establishing dominance or defending territory.In many species, communication behaviors are important in establishing dominance in a social hierarchy or defending territory.

- Coordinating group behaviors.In social species, communication is key in coordinating the activities of the group, such as food acquisition and defense, and in maintaining group cohesion.

- Caring for young.Among species that provide parental care to offspring, communication coordinates parent and offspring behaviors to help ensure that the offspring will survive.

As these examples show, communication helps organisms interact to carry out basic life functions, such as surviving, obtaining mates, and caring for young.

7 Simple Steps to Communicating With Your Animals

- Begin with a meditation that will give you a calm and tranquil mind. Seek out a pleasing and tranquil atmosphere for you and your animal.

- Ask your teachers and guides to help you with this process.

- Say your animal’s name telepathically to get his or her attention. That is, think of his or her name and visualize your animal as you say his or her name.

- Send a picture of his/her physical body. Direct this to him or her, along with your animal’s name.

- Ask if there is anything your pet would like you to do for him or her. Imagine your animal is sending an answer back to you through a picture, thought, sound, smell or feeling. Your imagination is powerful. Accept whatever you receive.

- Always acknowledge the answer, whatever you receive in your imagination, and thank your guides and your animal for their willingness to communicate with you in this way.

- Continue to ask your animal other questions, and remember to trust your imagination for what you are receiving back.

REFERENCE-ON REQUEST

https://www.pashudhanpraharee.com/concept-of-telepathy-or-animal-communication-its-importance/