DOGS RESTRAINING TECHNIQUES DURING EXAMINATION

Of all the species you’ll encounter, the dog will likely display the greatest range of reactions to restraint and handling.Some dogs are calm and cooperative; others respond aggres-

sively. These reactions can differ from the dog’s customary demeanor. Often a dog that’s docile and friendly at home

reacts differently in a veterinary hospital

Collars and leashes. —

Any dog you’re handling should wear

at least a collar, which allows easier control should the dog suddenly begin to resist. Several types of collars serve this purpose. Remember, whichever you choose, any collar must be the correct size. Most dogs can easily slip out of a collar that’s too large, and risk injury from a collar that’s too small.

(A growing puppy should receive new collars to accommodate its changing size.)

Types of collars and leashes.——

Training collars consist of

stainless-steel links with a ring at each end (Figure 1A). The

links can be a variety of thicknesses. In general, the thicker

links are used for very large, muscular dogs, while thinner links

are best for smaller breeds. Training collars are sometimes

incorrectly referred to as “choke” collars. A properly-used

training collar never chokes the animal. You must, however,

apply it correctly to avoid injuring the dog. Choose a collar

approximately two inches longer than the circumference of

the dog’s neck. The collar should slip easily but snugly over

the dog’s head (Figure 1B). The loose end, which takes the

leash, should come over the back of the dog at the top of, not

underneath, its neck (Figure 1C). Once the collar and leash

are in the appropriate position, you can lead the animal,

but never pull the collar tight. Apply short, firm tugs that

momentarily tighten the collar. Never leave a training collar

on an unattended dog. These collars catch easily on cage

bars and similar surfaces, and thus can seriously injure or

kill a dog.

Nylon or leather flat collars are most appropriate for daily

home use. However, don’t rely on a flat collar for restraint; dogs can easily slip out of them, and some flat collars are

designed to release quickly so that they don’t catch on something and choke the dog.

Any dog you’re leading should wear a leash (Figure 2). Leashes

can also aid restraint, and help to prevent animal-to-animal

contact in the waiting room. There are many kinds of dog

leashes on the market. Veterinary practices often use a slip

leash, one made of flat or braided nylon with a metal ring

at one end, on all patients. A slip leash applied prior to

examination may help to control a dog that resists handling

or escapes from its handler. A dog wearing a slip leash is

also easier to remove from a cage. Apply the slip leash as you

would a training collar. Many veterinary practices imprint

these inexpensive leashes with their practice name and give

them as gifts to new clients.

Leashes are also made of rope, nylon, chain, or leather, with

clips to attach directly to a collar. Leather leashes tend to be

quite expensive and are rarely used in veterinary practice.

Leashes come in many thicknesses and lengths. Always use thicker leashes on large dogs. A thinner leash may break if a large dog pulls against it. Shorter leashes are appropriate for moving animals from place to place in the veterinary practice; longer leashes allow the animal to exercise.

Muzzles——-

A muzzle is any device applied around an animal’s

nose and mouth to prevent the animal from biting. Any dog

that may become aggressive during examination or treatment

should wear a muzzle, applied before the animal shows signs

of fear or aggression. Muzzle application can also temporarily

distract a dog and allow you to complete a procedure. Several

types of muzzles are available; you can also improvise a

muzzle out of available materials. Whatever muzzle you choose,

take care that you don’t put it on any dog with signs of

breathing difficulties or chest injury. Also, make sure that

you don’t leave the muzzle on too long. Some muzzles prevent

a dog from panting, which it must do to avoid overheating.

Muzzles left in place too long can also injure the dog. Finally,

a dog that vomits while wearing a muzzle is likely to aspirate

the vomit.

Plastic, leather, or wire-basket muzzles are available in a

variety of sizes. This last type of muzzle is a small cup placed

over the end of the dog’s nose and clipped behind its ears.

Because these muzzles allow the dog to pant, you can leave

them on longer; some dogs, however, are able to bite through

this type of muzzle.

Nylon muzzles, more common in veterinary practice, slip over

the dog’s nose and clip behind the head (Figure 3). Some

nylon muzzles aren’t adjustable, but most veterinary prac-

tices keep enough sizes of them on hand to make the correct

size always available. Ensure the muzzle you choose fits

snugly but isn’t overly tight. Wash the muzzle promptly after

you remove it.

When you don’t have a commercial muzzle, you can impro-

vise your own from available materials. If the dog has a nylon or leather leash attached to its collar, create a temporary

muzzle by wrapping a portion of the leash around the animal’s mouth (Figure 4). Take care not to pull the leash

tightly. The leash should be just tight enough to keep the

animal from opening its mouth.

You can also make a muzzle out of gauze roll bandage. To make a gauze muzzle,

Step 1: Take a long piece of bandage and tie a large loop at

its midsection (Figure 5A).

Step 2: Approach the dog from the side or back and slip

the loop over the end of the dog’s nose (Figure 5B).

Step 3: Quickly tighten the loop and bring the ends of the

gauze under the dog’s neck (Figure 5C).

Step 4: Cross the ends over, then pull the ends behind the

dog’s neck (Figure 5D).

Step 5: Tie the ends of the gauze in a half bow or slip knot

so that it can be removed quickly (Figure 5E).

You must modify this technique for dogs with short or pug noses. For pug-nosed dogs, slip the loop over the dog’s nose with the tie under the jaw. Pull the ends of the gauze behind the ears, then tie them securely. One of the ends of the gauze should then be drawn down across the dog’s forehead and slid under the loop at the top of the nose, to keep the loop from slipping off the end of the dog’s nose.

Head snares——-

Vicious dogs should be caught and restrained

with a head snare, sometimes called a “rabies pole” or a

“restraint pole” (Figure 6A). The head snare is a long metal

or heavy-duty plastic tubular handle with a thick retractable

wire inside it. This wire is long enough for a large loop of it to

be pulled out, slipped over the dog’s head, and quickly tight-

ened (Figure 6B). The snare handle allows you to keep the

animal at a safe distance (Figure 6C). Once the snare has

served its purpose, a quick release mechanism loosens the

loop for easy removal from the dog’s neck. Dogs that are

especially strong may require two handlers, each with a head

snare attached to the animal, to lead the dog. Make sure that

the snare will release easily when necessary.

Whenever possible, allow a dog to approach you first. Often

a fearful dog simply needs reassurance that you aren’t a

threat. Crouch or kneel down on the floor and coax the dog

slowly (Figure 7). Verbally reassure the dog with a calm,

cheerful tone of voice. Allow the dog to approach voluntarily.

If you must approach a dog, always do so carefully and

slowly. Make sure that the dog can both see and hear you

coming. Observe the dog closely for any signs of fear or

aggression. Slowly hold out your hand, making sure that

your hand is no higher than the dog’s nose. The dog may

perceive gestures above its nose as threatening, and respond

aggressively. Above-the-nose gestures include bending over

the dog or attempting to pat its head when it’s still unsure of

you. Once the dog has approached you and is accepting your

handling without signs of fear, you may slip a leash over its

neck or lift it onto the examination table.

picking up and carrying a dog.——-

The proper method of

picking up and carrying a dog depends upon the dog’s size

and health. Two prerequisites before picking up a dog: apply

a leash, and crouch beside the animal. The leash helps pre-

vent the dog from escaping. The crouch spares your back.

Lifting even a small dog from a standing position can injure

your back. To lift a small, uninjured dog, which weighs less

than 50 lbs,

Step 1: Place one arm under the dog’s head.

Step 2: Place your other arm under the dog’s abdomen

with your hand pointed forward and your fingers

between the dog’s front legs.

Step 3: Lift the dog straight up and place it on the examin-

ing table.

You can even carry small dogs in this position. To lift a small dog that’s injured or may be injured,

Step 1: Place one arm under the dog’s head (Figure 8A).

Step 2: Place your other arm around the dog’s hind-

quarters (Figure 8B).

Step 3: Lift the dog straight up and place it on the examin-

ing table (Figure 8C).

Taking a dog from its owner.——-

Some dogs are very protective of their owners, and may respond more aggressively than they would in the owner’s absence. Follow the same approaching guidelines when you approach a dog that’s with its owner, but also make sure that you talk in a reassuring tone to both dog and owner. Be especially careful not to make sudden movements. Look at the dog, but don’t stare. Some dogs

interpret staring as a threat or challenge.

Take the dog’s leash from its owner and ask the owner to

walk away from the dog. If you must lead the dog away from the owner, coax the dog with a cheerful and calm tone.

Removing a dog from a cage.———

Before you remove a dog from

a cage, find out if the dog can stand and walk. If it can, and

it has no neck, throat, or aggressiveness problems, partially

open the cage door and put a slip leash around the dog’s

neck (Figure 10). The leash prevents the dog from escaping

once the cage door is fully opened; it also permits some con-

trol should the dog become aggressive. To slide a slip leash

over the dog’s neck without fully opening the cage door, wait

at the front of the cage and let the dog approach you. If the

dog is small and docile, grasp it by placing one arm under

its body and the other arm under its neck (Figure 11). Place

the slip leash while holding the dog in this position. If the

dog is small but aggressive, place a blanket or towel around

it before lifting.

Uncaging larger, more aggressive dogs usually requires special handling. Many veterinary practices keep these dogs leashed, with the leash slipped through the bars of the cage door, which allows the handler to move the dog toward the door by gently pulling the leash. This technique keeps the door between the handler and a dog that may try to bite.

If the dog can’t walk or stand, a leash is unnecessary; gently

lift the dog from the cage. For animals with neck or throat

problems, use a chest harness instead of a leash. You may

also need to remove the leash and apply a harness if the

leash interferes with a medical device, like an intravenous

catheter, to be placed in the dog’s jugular vein.

The appropriate restraint method for a dog depends upon

what the veterinarian is doing, and upon its overall tempera-

ment. Veterinarians perform most dog examinations and

treatments on a table; your job is to keep the dog in position.

Standing restraint———

. Veterinarians often complete routine

physical examinations with the dog standing. To maintain a dog in a standing position,

Step 1: Place one hand in front of the dog’s neck (Figure 12A).

Step 2: Place the other hand under the dog’s abdomen just

in front of its rear legs (Figure 12B).

Step 3: Gently pull the dog toward you until it’s snug

against your body (Figure 12C).

Hold this position until the examination is complete. As

usual, practice the minimum necessary restraint; being held too tightly can make some dogs fearful.

A variation of this standing-restraint technique is to place

your second arm around the dog’s hindquarters rather than under its abdomen. While this technique gives you more control over the dog, it may interfere with some procedures, like rectal examination.

Sitting restraint.———

Some dogs require restraint firmer than

you can obtain with the standing position. For these dogs,

you can employ sitting restraint. The sitting position is also

appropriate for most routine injections and some minor tech-

nical procedures. To perform sitting restraint on a dog,

Step 1: Place your arm around the dog’s hindquarters

(Figure 13A).

Step 2: Gently tuck the dog into a sitting position

(Figure 13B).

Step 3: Place your other arm around the dog’s neck so

that its head rests in the crook of your elbow

(Figure 13C).

Step 4: Pull the dog snugly against your body (Figure 13D).

Restraining puppies———.

You can restrain puppies much as

you would adult dogs, but with a much gentler touch.

Whenever possible, remove the bitch from the room before

any examination or treatment of her puppies. If for some reason you can’t remove the bitch, keep her puppies as calm as possible. A puppy that makes vocal signs of pain or distress may cause the bitch to attack.

Restraint of injured or ill dogs. ————

Handle a severely ill or

injured dog as if it’s likely to bite. Many times a severely injured

or ill animal responds out of extreme pain, and biting is a dog’s

major defense against pain. Take extra precautions when

handling any injured animal. To prevent a human injury,

place a muzzle on an injured animal. You may, if necessary,

place a towel or blanket over a particularly violent animal to

calm it. Just make sure you move the dog to a proper examina-

tion area promptly—this draping technique often produces

only a brief period of calm.

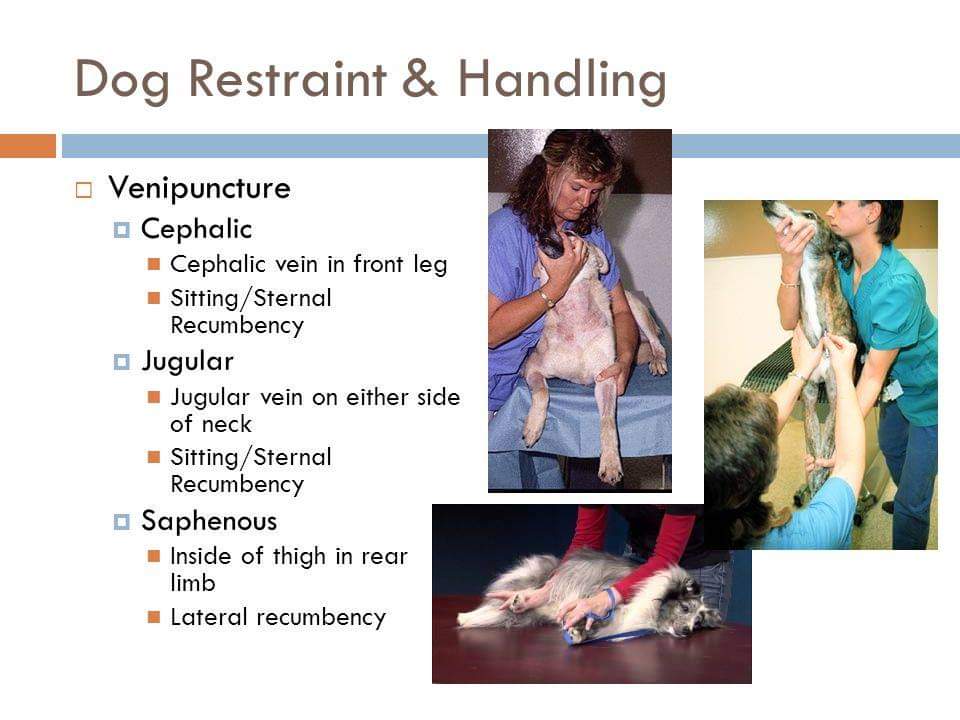

Dog restraint for venipuncture.————

Venipuncture, puncturing

a vein to collect blood or administer medication, requires

careful and firm restraint. A dog that struggles during

venipuncture could damage the vein. Restraint techniques

for venipuncture vary depending upon the vein. A dog’s most

common venipuncture sites are the cephalic vein, along the

front of the dog’s foreleg (Figure 15); the saphenous vein, on

the outer surface of the dog’s hindleg (Figure 16); and the

jugular vein, on the front of the dog’s neck (Figure 17).

Venipuncture restraint requires careful positioning so that

the vein is accessible and the dog can’t move. You may also

be expected to occlude the vein (block the vein’s circulation

by pressing on it with your finger). Occluding or “holding off”

the vein pools blood in the vein, allowing it to be easily seen

and felt. Occluding the vein also provides enough blood for

proper venipuncture.

A dog undergoing cephalic venipuncture is usually placed on

its sternum (breastbone) on the examination table, its forelegs

extending slightly over the table’s edge (Figure 18A). This type

of restraint is called sternal recumbency. To restrain a dog for

cephalic venipuncture,

Step 1: Stand at the side of the table, facing in the same

direction as the dog.

Step 2: Grasp the dog under its neck so that its head rests

in the crook of one elbow (Figure 18B).

Step 3: Place your other arm across the dog’s back and

pull the dog snugly against your body (Figure 18C)

Step 4: Extend the same arm to grasp the dog’s opposite

forelimb at elbow level with your right hand.

Step 5: Hold the forelimb at the elbow and use your thumb

to occlude the vein by pressing in and slightly to

the side (Figure 18D).

The dog’s elbow should be at the table’s edge, which allows

the veterinarian or veterinary technician to grasp the dog’s

foot and complete the venipuncture (Figure 18E). Should the

dog struggle, reassure it with a firm voice and hold it a bit

more tightly. You may also try distracting the dog by lightly

scratching the side of its head with yoThe dog may experience momentary pain when the vein is

punctured. Don’t release the animal from your grasp, or

remove your hand from its leg, until the venipuncturist tells

you to (Figure 18G). A veterinarian or veterinary technician

withdrawing blood or administering medication will tell you

when it’s time to release the occlusion of the veinur left hand (Figure 18F Once the needle is removed from the vein, maintain your

grasp on the leg and place your thumb over the injection site to prevent further bleeding. Applying pressure at this site helps the blood to clot.

Step 6: Maintain your grasp on the leg and simply lift your

thumb straight off it. Place your thumb over the

injection site while applying pressure. Continue to

hold the dog firmly.

Step 7: Once the procedure is complete, slowly loosen your

grip. Maintain moderate restraint to keep the dog

from jumping off the table.

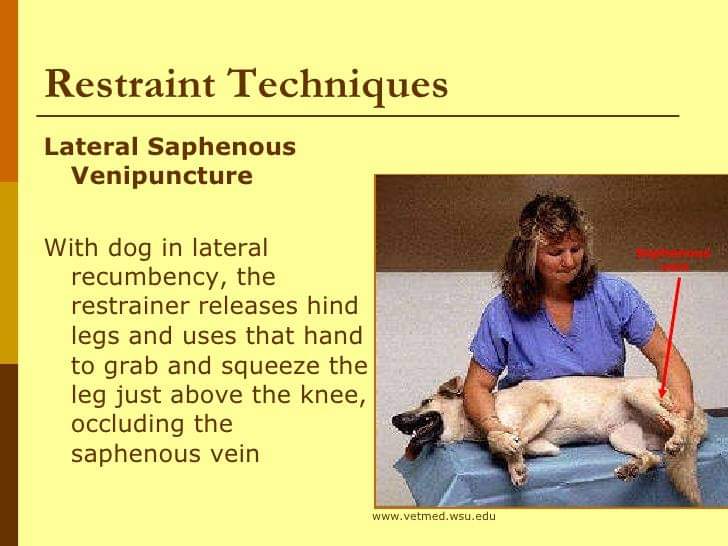

Restraint for saphenic venipuncture often requires that the dog be restrained in the lateral recumbent position (as do some x-ray examinations and technical procedures). To restrain a dog for saphenous venipuncture,

Step 1: Position the dog in lateral recumbency (Figure 19A).

Step 2: Grasp the upper rear leg just below the knee so

that the skin over the vein is pulled tight to

occlude the vein and prevent it from “rolling” while

venipuncture is being made (Figures 19B and 19C).

Step 3: Release the vein when directed by the veterinarian

or veterinary technician. By using this procedure,

medication can be administered or a catheter can

be passed into the vein.

Step 4: Apply pressure to the venipuncture site to allow

a clot to form and bleeding to completely stop

(Figure 19D).

Step 5: Once the procedure is complete, maintain moderate

restraint to keep the dog from jumping off the table.

It’s often helpful, should the dog struggle in this position, to

raise the legs closest to the table so that they cross the upper

legs.

Jugular venipuncture, like cephalic venipuncture, positions the dog on its sternum at the table’s edge with its forelegs extending off the table (Figure 20A). To restrain a dog for jugular venipuncture

Step 1: Stand alongside the dog and place your right hand

under its muzzle.

Step 2: Point the dog’s head toward the ceiling. You may

have to hold the dog’s mouth closed with your

hand (Figure 20B).

Step 3: With your left hand, grasp the dog’s front legs just

above the feet and hold them together. Secure your

grip by placing a finger between them (Figure 20C).

Step 4: Pull the feet slightly to align them with the dog’s

nose. The venipuncturist will normally occlude the vein without further assistance (Figure 20D).

Step 5: Once the procedure is finished, apply pressure to

the venipuncture site.

Bring on the dogs—you’ve now covered the basics of dog

restraint. However, what about cats? If you’ve spent any time

around them at all, you know some of the challenges cats

present. It isn’t easy, but yes, it’s possible to restrain our

feline friends.

Before moving on to cat restraint, take a few moments to complete

Compiled & Shared by- Team, LITD (Livestock Institute of Training & Development)

Image-Courtesy-Google

Reference-On Request.